Tale spodnji povzetek kitajske gospodarske strategije bi morali predavati na vseh poslovnih šolah in vse vlade in parlamenti širom sveta bi se morale na nujnih sejah s tem seznaniti. Medtem ko zahodne države prek velikih medijev že več kot dve desetletji spinajo, da je Kitajska tik pred razsulom, da se bo ujela v “past srednjega dohodka” in da mora dati večjo vlogo potrošnji BDP namesto investicijam, se Kitajska pospešeno tehnološko razvija in industrializira. Medtem ko so zahodne države v zadnjih desetletjih šle v deindustrializacijo in krepitev storitvenega sektorja, predvsem finančnega, temelji sedanji kitajski 5-letni načrt na pospešeni industrializaciji. Medtem ko so zahodne države v zadnjih desetletjih v pohlepu korporacij po dobičkih šle v deindustrializacijo z oblikovanjem globalnih dobaviteljskih verig (verig vrednosti) in bile zadovoljne s prenosom “nižjih faz proizvodnje” (proizvodnja materialov in fizično sestavljanje izdelkov) v manj razvite države ter zadržanjem “višjih faz proizvodnje” (R&R, dizajn, marketing, prodaja, finance), Kitajska stremi k oblikovanju kompletnih verig vrednosti. Torej želi imeti doma pod nadzorom celotno verigo vrednosti v proizvodnji. Ob tem, da krepi tehnološki razvoj in dizajn, želi obdržati tudi industrijsko bazo, ki je temelj strateške avtonomije, hkrati pa s strateškimi meddržavnimi dogovori in investicijami v tujini kontrolira ključne naravne vire (energijo, ključne surovine in materiale).

Prihajamo v situacijo, da tako enostavnega proizvoda, kot so sončni paneli, zahodna podjetja ne bodo sposobna avtonomno proizvesti, ker brez Kitajske ne bodo imela na voljo ključnih inputov zanj.

ZDA so sicer zagnale paniko in po letu 2018 poskušajo z različnimi nelojalnimi praksami (v nasprotju s pravili WTO) Kitajsko zaustaviti. Vendar je to jalovo početje. Kitajska ima 1.4 milijarde ljudi in je, v primeru morebitne totalne vojaške eskalacije, sposobna zagotoviti dovolj velik trg za potrebe ekonomij obsega v industriji in razvoju. Hkrati si je Kitajska s strateškimi povezavami (SCO, BRICS+), meddržavnimi dogovori (Rusija, Savdska Arabija, Iran, Kazahstan) in investicijami v nahajališča in proizvodnjo ključnih materialov zagotovila dostop do energije in vseh ključnih materialov za proizvode prihodnosti. Kitajska ima velikost in strategijo, ki sta v kombinaciji nepremagljivi. In ima politično vodstvo z neskončnim časovnim horizontom namesto zahodnih kratkoročnih horizontov v okviru štiriletnih poliitčnih ciklov.

Zahodne države za nekaj korakov zaostajajo za Kitajsko. Vprašanje je le: bodo zahodne države poskušale posnemati Kitajsko v razvojni strategiji (industrija, tehnološki razvoj, zagotovitev dostopa do poceni energije in kontrola proizvodnje ključnih materialov) ali pa jo bodo poskušale v obupu zaustaviti z vojno?

Slednje je slaba strategija, ki se ni izšla niti proti 150-milijonski Rusiji brez resne industrijske baze (razen v orožarski industriji). Pri 1-4-milijardni Kitajski v navezi z Rusijo in BRICS+ je to zahodni samomor.

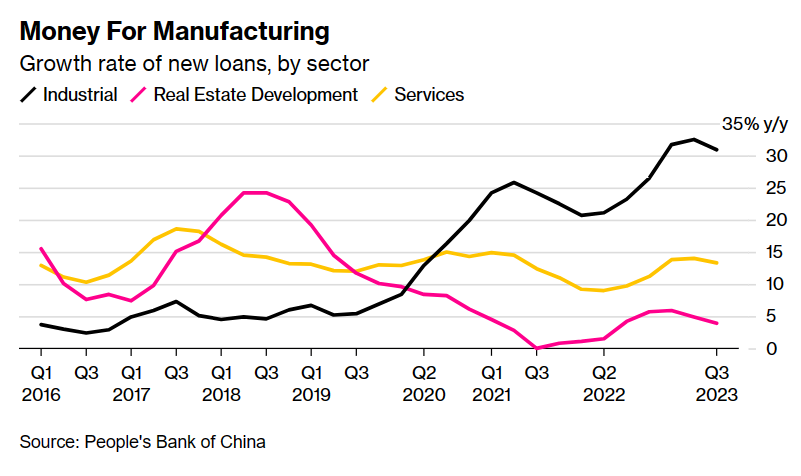

A new Bloomberg article has insightfully broken down China’s strategy to go well above middle-income status, avoid technological blockades, proceed with high-tech industrial upgrades and take center-stage in the World Economy while completely refuting the Neoliberal Orthodoxy in the process. As is well known by now, China has consciously and intentionally deflated its Property Sector and non-productive service industries such as Private Tutoring and Gaming; and has funneled that credit toward Industrial development.

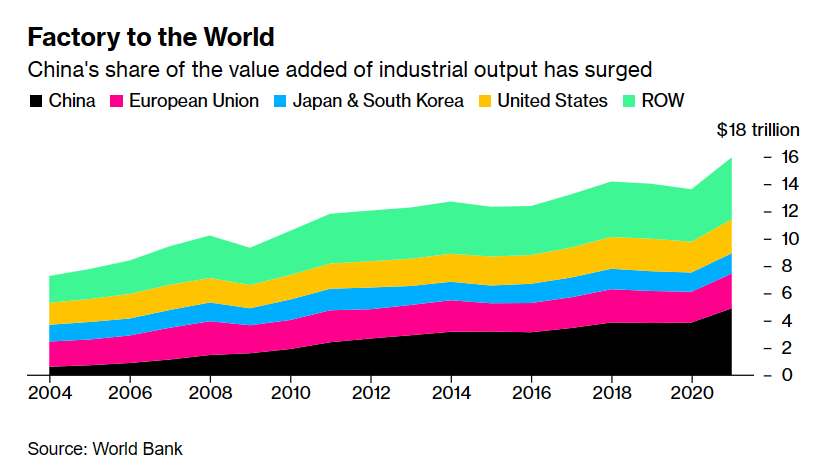

The consequences of this are astounding. China’s surplus of manufactured goods relative to global GDP is now 2%, a level unseen since the US after World War II, when all Europe and Japan lay in ruins. But, unlike wartime destruction, the de-industrialization of the West was entirely self-inflicted. It sought to alleviate (or do away with) the social and economic pressures of a highly organized and politically conscious working class by exporting industrial manufacturing and the contradictions that come with it. As a consequence, Bloomberg estimates that 45% of China’s gargantuan manufacturing output (now accounting for more than 1/3rd of global value-added) is exported. But we have long since passed the era of cheap Chinese toys and clothes. China is now competing for the whole cake and biting the heels of Germany, South Korea and Japan, cutting into the they have historically held against China due to their essential provision of hi-tech components that China was unable to make by itself.

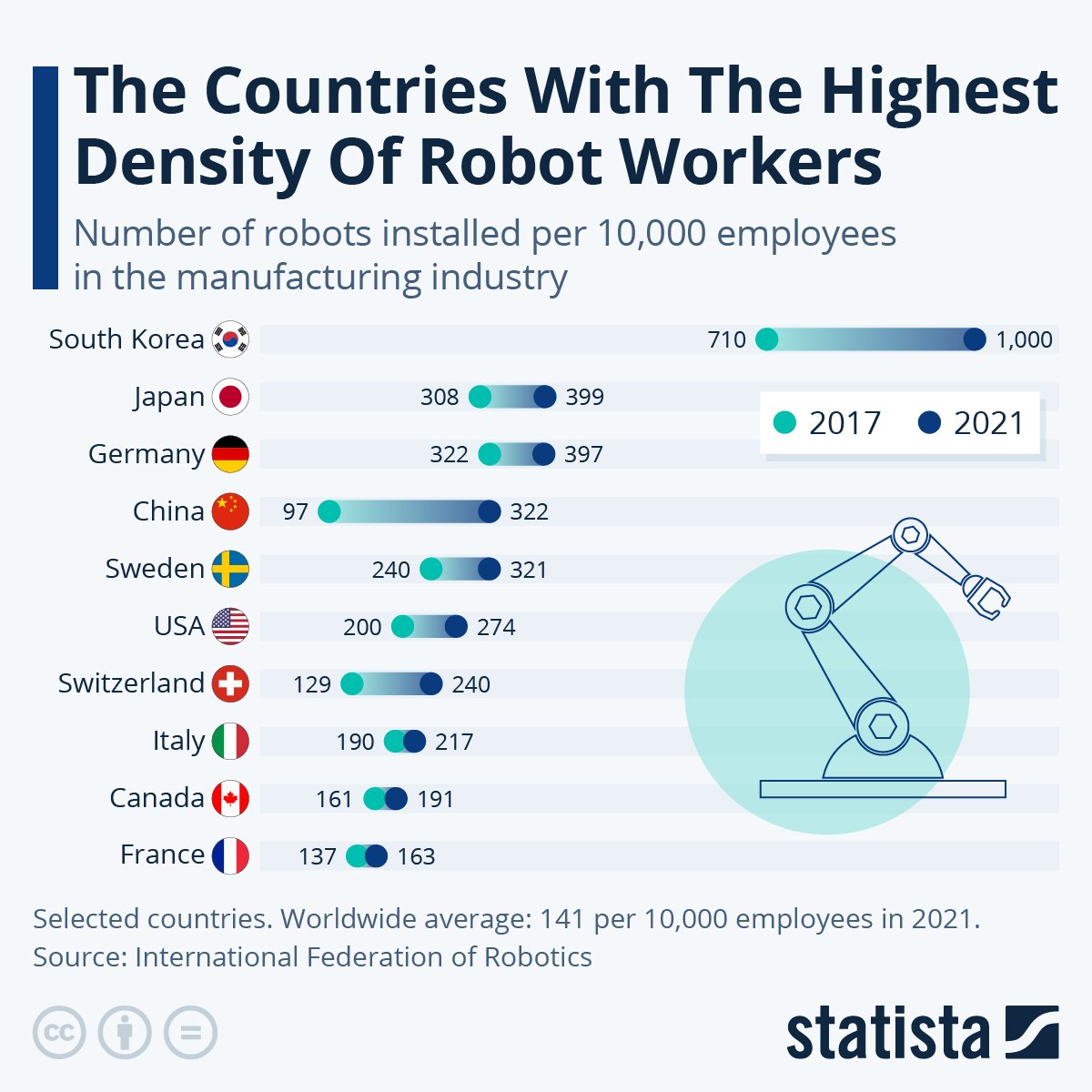

But that reality has changed. China’s large-scale campaign of industrial upgrading is already bearing fruit. This can be seen by the massive trend toward robotization. China’s manufacturing industry is now more automated than Sweden, America or Switzerland’s and it will soon surpass (or has already surpassed) Japan and Germany, leaving only south Korea (and the much smaller Singapore; not listed in the chart) as competition.

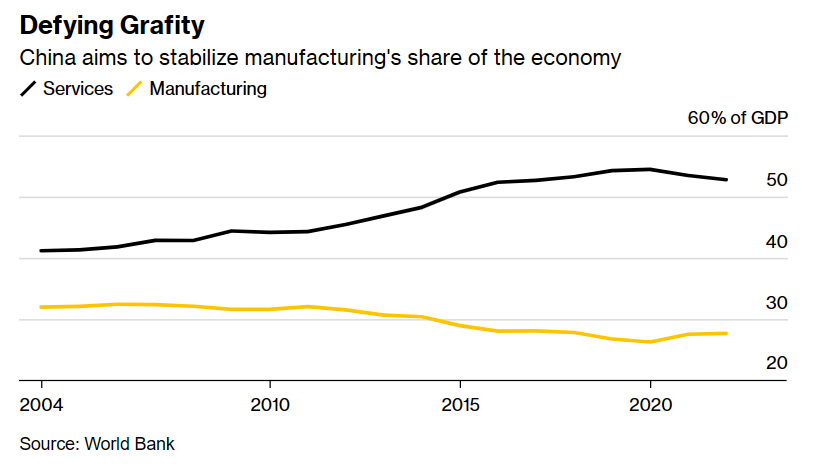

Despite all the talk of “China’s economic slowdown”, there is one metric that doesn’t lie: commodity prices (in the sense of raw materials and basic goods) as they are actively increasing, despite the slowdown in Real Estate construction; China’s New industrial campaign is more than making up for that lost demand, although its further evidence will not be short-term bursts of double-digit growth, but a long structural trend toward high-quality, medium-speed growth. In short, there will be no Japanization. Instead, Arthur Kroeber of Gavekal Dragonomics uses the amusing but apt term of a “Leninist Germany”; although with China we speak of a “Germany” with 17 times the population, or more than the entire Developed World combined. China is thus defying the neoliberal doctrine of an ever-expanding Service sector. In its latest Five-Year Plan, it has stated in no uncertain terms than from 2020 onward, the share of GDP represented by manufacturing *will not be allowed to decrease*, and has since risen to 28% from a 26% low.

Additionally, China is challenging another neoliberal orthodoxy: hierarchical value chains. It seeks to become industrially self-sufficient; it will not let go of lower-end industries entirely and rely on Africa or Southeast Asia the way the West has relied on China. Xi and the current generation of leadership understand that his path is not only treacherous to economic and national security but would carry with it massive social challenges linked to destruction of livelihoods.

Furthermore, it is unnecessary. 1/5th of the world population with ever-increasing degrees of education and automation need not rely on the exploitation of the cheap labor of others. This is the underlying reason for the massive push toward robotization. “To build a complete supply chain” as Damien Ma puts it.

According to China Briefing, China is the only country that possesses all the industrial categories in the UN’s industrial classification. Here we see a reflection of an unavoidable fact: China is an entirely different kind of power. There is zero precedent for a civilization-state who strives for a simultaneously major presence in the World Economy (external circulation) and a complete domestic industrial supply chain at the cutting edge of technological and industrial development (internal circulation) but this is what is entailed by the Dual Circulation policy and the shift toward Domestic Demand, Manufacturing and New Energy industries as the mainstay of Chinese economic development over the coming years. The political-economic uniqueness of this will strike many as novel, particularly those few but annoying voices on the “Left” that seek to draw parallels between China’s rise and that of the Imperialist West.

Instead, one of the major contradictions will be between the declining, post-industrial West as it seeks to hold onto its hegemonic position at the top of global supply chains (it has already completely lost in areas such as EV manufacturing, Solar Panels, etc…) by blocking China from competing in our own markets, after decades of our companies’ access to theirs. This will be one last attempt at choking out China and its ability to bring 1.4 billion people into the Developed World, thus doubling its population. It is a class struggle on a civilizational scale. Such renewed Trade Wars — with possible proxy military fronts if a more hawkish leadership takes hold of the reigns of government in the US — would inevitably require China to re-focus more heavily on domestic-demand-driven industrialization, a somewhat slower path to deal with industrial overcapacity, but this too would have positive long-term effects on China by forcing an even faster rise in Chinese incomes.

Its bet on manufacturing is a sure-fire way to preserve long-term economic and social stability. Bloomberg points out that:

“A 2017 study published by Singapore’s Ministry of Trade and Industry found every 100 new manufacturing jobs are associated with 27 new non-manufacturing jobs; by contrast, every 100 new service jobs are associated with only 3 additional manufacturing jobs. It also has the highest innovation potential, accounts for the bulk of economy-wide R&D spending and employs the majority of scientists and engineers.”

Fundamentally, the Real Economy will always triumph over the Virtual. China understands this and, unlike the West, already has a highly competent political system with an advanced class character capable of handling the challenge of building a new energy-based industrial modernity on a scale only comparable to the rise of the West and its offshoots; but in a span of 50, not 500 years. These political-economic changes are bound to shake up the global chessboard and, as I’ve pointed out in previous posts, already are from Novorossiya to Palestine to Myanmar. But we can only have a solid grasp of these geopolitical outbursts if we understand their geoeconomic foundations.

Vir: Orikron