Lamentacija iz Der Spiegla: nemška podjetja zaradi pomanjkanja plina (začasno ali trajno) zapirajo obrate, zaradi perspektive visokih cen energije na srednji rok opuščajo investicije doma, druga investirajo raje v države z nižjimi cenami energije, enako tuja podjetja (kot je Tesla) opuščajo načrte investicij v Nemčiji. Deindustrializacija je tu.

Vendar da se ne bi kdo “pametno” pridušal, da je ta proces odmiranja “stare” in energetsko intenzivne industrije pozitiven proces, ki ga bo nadomestila “nova” in energetsko manj intenzivna industrija: brez plina in brez ustrezno nizke cene energije tudi “nove” industrije (denimo, da jo ponazarjajo e-avtomobili in vse povezano z e-mobilnostjo in digitalizacijo) ne more biti. Proizvodnja baterij je energetsko izjemno intenzivna. In proizvodnji električne energije ali vodika, ki naj bi poganjala vozila prihodnosti, sta energetsko izjemno intenzivni. Dovolj in poceni energija sta predpogoja tako za razvoj “nove” industrije kot tudi za uporabo njenih proizvodov. Zato se zna zgoditi, da je nemška prihodnost že preteklost.

V teh nemških strokovnih debatah in časopisnih analizah me najbolj preseneča, da ob lamentiranju zaradi konca nemške industrije praktično nihče (s častno izjemo Clemensa Fuesta, direktorja inštituta Ifo) ne omeni primarnih vzrokov za to ter ali so sploh izpolnjeni drugi pogoji za novo, “zeleno” industrializacijo.

Prvič, pomanjkanje plina v Nemčiji je posledica tega, ker Nemčija (precej pred začetkom ukrajinske vojne) ni želela odpreti novozgrajenega plinovoda Severni tok 2, nato pa ker je po začetku sankcij Ukrajina zaprla en krak ruskega plinovoda proti Nemčiji, Poljska je zaprla plinovod Jamal, Nemčija pa zaradi sankcij ni želela dobaviti servisirane turbine za Severni tok 1 (šele nato, pred kratkim je Putin pristavil svoj del zapiranja pipice). Visoke cene električne energije pa so zaradi dobrega desetletja nemške “zelene blaznosti”, ko so zapirali stroškovno najbolj ugodne in najbolj stabilne energetske vire (jedrska), vlagali v izjemno drage obnovljive vire, hkrati pa je po želji Nemčije Evropska komisija za subvencioniranje vlaganj v obnovljive vire energije določila formulo za ceno električne energije, ki temelji primarno na ceni plina in premoga ter CO2 kuponov, in ki temu primerno podraži ceno električne energije. Zaradi subvencioniranja vlaganj v obnovljive vire energije so nemška gospodinjstva in podjetja zadnje deseletje plačevala v povprečju za 70% višje cene elektrike kot francoska. Letos pa so cene poblaznele zaradi visokega povpraševanja in strahu pred pomanjkanjem pliona. Drugače rečeno, za pomanjkanje plina in za visoke cene energentov si je kriva Nemčija sama. Sama je lastnoročno poskrbela za to. Za sedanjo deindustrializacijo v Nemčiji so krive predhodne in sedanja nemška vlada, ki so ustvarile pogoje zanjo.

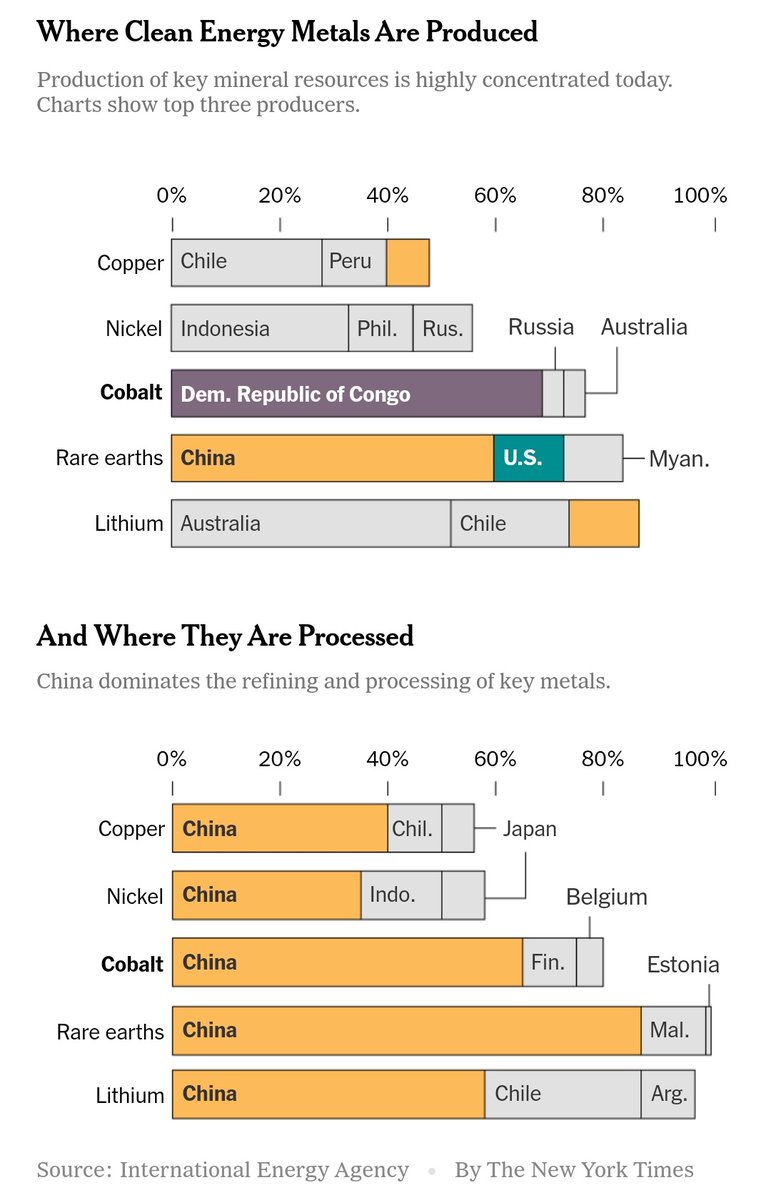

In drugič, ali so drugi pogoji za novo industrializacijo res izpolnjeni v obdobju deglobalizacije? Razvite države so začele najprej s trgovinskimi, zdaj pa še s tehnološko vojno proti Kitajski. Kitajski želijo odvzeti premoč v proizvodnji proizvodov “nove industrije” – od baterij do čipov. Toda Kitajska nadzira predelavo tako večine surovin za “zeleno industrijo” – od bakra, niklja, kobalta, redke zemlje do litija (glejte sliko spodaj) …

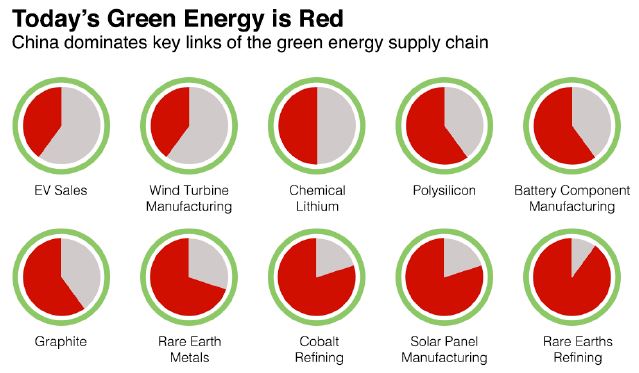

… kot tudi nadzira proizvodnjo ključnih inputov in dobršen del ali večino končnih izdelkov “zelene industrije” – tretjino proizvodnje e-vozil in vetrnih turbin, 60% komponent za proizvodnjo baterij ter 80% solarnih panelov (glejte sliko spodaj).

Nemški industrisjki model, stari ali novi, temelji na globalizaciji – na prostem dostopu do uvoza vseh komponent in na prostem dostopu na trge za končne izdelke. Če ukinemo globalizacijo, tako da omejimo Kitajsko, Nemčija nima več dostopa do ključnih komponent za razvoj svoje “zelene industrije”.

Torej, nemški industrialci, ko boste spet lamentirali o šoku zaradi deindustrializacije, morate prst uperiti v nemško vlado. Ta je kriva za pomanjkanje in visoke cene energentov in ta edina lahko spremeni kurs Evropske komisije tako glede politike do Kitajske kot glede politike sankcij proti Rusiji. Ali pa tudi ne.

____________

But what happens if companies decide that this dual effort – overcoming the energy crisis and restructuring the economy – isn’t worth it? That the two challenges together are simply too expensive?

The Kirchhoff Group has been active in Germany since 1785 and is one of the country’s most important auto parts suppliers. They produce such divergent products as aluminum covers for the batteries in Volkswagen’s electric cars and crash-management systems for some BMW models. The company is well established.

The automobile sector in Germany could be hit all the harder if companies like Kirchhoff run into difficulties. “In the coming months, we will start seeing who can even still afford to produce in Germany,” says Arndt Kirchhoff, chairman of the advisory council for the family-owned company. It used to be that electricity and gas made up 3 to 4 percent of company’s costs. Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, that share has skyrocketed to 12 percent. “In a situation like that, investments in Germany are no longer worth it,” says the 67-year-old.

Kirchhoff is a global player with revenues of 2.2 billion euros and also operates factories in the United States, Mexico and China. In those places, there is plenty of cheap energy, which makes it easier for Kirchhoff to manage risks associated with any one location. Which is what the company is doing. Here in Germany, Kirchhoff is merely keeping its machines running, but isn’t planning any new facilities.

But there are plenty of suppliers that don’t have a global network of production sites, and they are in a much more difficult spot. According to a recent survey conducted by the German Association of the Automotive Industry (VDA), 10 percent of companies in the sector say they are suffering from liquidity problems. An additional 32 percent are forecasting financial shortfalls in the coming months. The 103 companies that took part in the survey said that the biggest burden they are currently facing is the price of energy. More than half have reacted by delaying or cancelling planned investments. The situation of small and medium-sized companies (SMEs), in particular, is “becoming increasingly dramatic,” says Hildegard Müller, the VDA president.

Even VW, which raked in record profits in 2021, is sounding the alarm. “We depend heavily on the strong supply industry that we have,” says Supervisory Board Chairman Hans Dieter Pötsch. If Europe were to lose this industrial structure, “then it would also lose its competitiveness” – unusually drastic words from a powerful man who rarely speaks in such a manner.

Some companies are already being pushed by their financial backers to invest outside of Europe due to the energy crisis. In the worst case, even the multibillion euro shift to electric mobility could be in danger. “For e-auto drivers, there must be a sufficient quantity of affordable electricity available,” says Pötsch.

A dangerous tendency could develop. The automobile industry in particular must invest huge sums in the coming years. Why not use the opportunity to move production sites to places where energy is already far cheaper? Or to places where renewable energies will soon be available in large quantities?

Should that happen, then the current situation is no longer a question of a couple of difficult years, but of the sources of the country’s future prosperity. After all, that prosperity is supposed to come in part from energy-intensive technologies such as battery cells. Volkswagen alone plans to invest 20 billion euros in Europe in battery production, and even the Chinese global leader CATL intends to build a gigafactory in the German state of Thuringia. Such plans could be “reconsidered and recalculated,” warns Ferdinand Dudenhöffer, director of the industry think tank Center Automotive Research. Putin’s energy war could currently be in the process of destroying “the vital establishment of the new automobile industry” in Germany.

Last Wednesday a report in the Wall Street Journal shocked the sector, according to which Tesla has decided to suspend plans for building a battery factory outside of Berlin, preferring instead to focus production in the U.S. Is Germany’s future already in the past?

The sector is still hoping to avert such a fate. VW insists it is staying true to its investment plans. “We need our own battery factories for the mobility and energy revolution in Europe,” says advisory board chair Pötsch. At the same time, though, he is demanding immediate political action so that Europe doesn’t lose its competitiveness. Energy prices, he says, must be capped for the next couple of years.

That demand, to put it mildly, sounds kind of odd coming from a senior executive in a capitalist economy. And it is one that begs the question: Have company and political leaders made mistakes of their own in the last several years? Did they contribute to the country suddenly being so vulnerable? Did everyone underestimate just how sensitive this phase of transition might be?

Fuest, the economist, believes that Germany’s cardinal error was that of disassembling its energy system based on nuclear, coal and gas power before the new system, based on renewable energies, was ready. That is the primary cause of the insecurity felt by industrial companies, a feeling that has been magnified by the current gas and electricity price catastrophe.

It is likely also true that the transformation has proceeded far too slowly, to the point that nobody can say when our dependency on fossil fuels might come to an end. Which means that nobody can make any reliable predictions regarding how much we might be paying for gas and electricity a few years from now. “As such, companies should be shifting into crisis mode,” says consultant Henzelmann. “And you don’t run away in a crisis.”

What has already become apparent is that this crisis is shaking the very foundations of our economy. Whereas the pandemic reserved its most deleterious effects for restaurants and cultural offerings, Germany’s industrial giants are on the front lines this time, gigantic companies with complex processes. Restaurants are relatively easy to close down and open back up again. Chemical factories are not.

Markus Steilemann is head of the chemical company Covestro. A former Bayer subsidiary, Covestro produces plastics from oil-based raw materials that find their way into car headlights, foam mattresses and building insulation. There is hardly another company out there that is as dependent on gas and oil as Covestro. The enterprise is doing all it can to rely more heavily on materials that use more biomass than oil. It is conducting research into recycling foam mattresses and is capturing CO2 to use it for the production of plastic. And yet the vast majority of the company’s production still depends on oil and most of the electricity and steam they use comes from natural gas-fired power plants.

Steilemann fluctuates between optimism and despair. The end of natural gas deliveries from Russia “could result in production sites in Germany losing their competitiveness,” he says. On the other hand, though, high prices for natural gas don’t automatically spell the end for all energy-intensive industry in Germany. Whereas some prices, such as that for primary products used in manufacturing synthetic fertilizers, are up to 80 percent dependent on the cost of natural gas, it plays only a minute role for highly specialized chemicals, says Steilemann.

Chemical industry giants aren’t likely to leave the country anyway. Their processes are simply too complex and the companies are too intricately connected to other companies. Even global market leader BASF isn’t thinking seriously about leaving Germany, despite the fact that no other factory in the country uses as much natural gas as does BASF’s plant in Ludwigshafen. BASF has reduced the amount of ammonium it produces and is purchasing it on global markets. But because the production of numerous different chemicals is intricately linked in its factories, making them highly efficient, it makes little sense to break off individual, highly energy intensive steps in the process and take them out of the country, the company says.

Plus, BASF and other chemical companies have production facilities on every continent, making the products that are needed there. If the European economy is laid low for an extended period, though, chemical companies are likely to expand capacity elsewhere. BASF is currently in the process of building a new, 10-billion-euro factory in China. Any shift out of Germany for the chemical company seems likely to be more gradual in nature rather than a sudden bang.

So does that mean that the country will see its industry fade away in slow motion in the coming years?

Vir: Der Spiegel

You must be logged in to post a comment.