Spodaj je zelo dobro dokumentirana finančna analiza, ki kaže, da medijska kampanja o finančnem in gospodarskem zlomu Kitajske ne drži. In analiza tudi daje odgovor, zakaj zahodni mediji to kampanjo izvajajo prav zdaj, ko se v resnici sesuva ameriški obvezniški trg.

It is impossible to turn to a newspaper, financial television station or podcast today without getting told all about the unfolding implosion of the Chinese economy. Years of over-building, white elephants and unproductive infrastructure spending are finally coming home to roost. Large property conglomerates like Evergrande and Country Garden are going bust. And with them, so are hopes for any Chinese economic rebound. Meanwhile, the Chinese government is either too incompetent, too ideologically blinkered, or simply too communist to do anything about this developing disaster.

Interestingly, however, financial markets are not confirming the doom and gloom running rampant across the financial media. Consider the following points.

Bank shares

At Gavekal, we look at bank shares as leading indicators of financial trouble. When we see bank shares break out to new lows, it is usually a signal that investors should head for the exit as quickly as possible. This was certainly the case in 2007-08 in the US. Between February 2007 and July 2008 (six weeks before the collapse of Lehman Brothers), banks shares lost -60% of their value.

The same pattern unfolded in Europe. Between January 2010 and August 2011, eurozone bank shares fell -45%, collapsing to new lows even before Club Med spreads started to blow out.

Now undeniably, Chinese bank shares have not been the place to be over the past few years. Nonetheless, Chinese bank shares are still up a significant amount over the last decade. And this year, they have not even taken out the low of 2022 made on October 31st following the Chinese Communist Party congress. To be sure, the chart below is hardly enticing, even if the slope of the 200-day moving average is positive. Still, Chinese bank shares do not seem to be heralding a near-term financial sector Armageddon.

Digging further, if we look at the performance of Chinese bank shares relative to US and EU bank shares over the past five years, the banks of the world’s three major economic zones have delivered roughly similar share price performance.

Zooming in on performance over the past year seems to indicate that if there is a problem with banks, it lies more in the US than in China, where bank shares are flat year-to-date. So, if you were to look only at the charts, you would conclude that the weak link in the system is not Chinese banks but US regional banks. In the past five years, US regional banks have registered two massive sell-offs—the kind of sell-offs that make shareholders uneasy.

Chinese equity markets

Given the relentless media negativity, you might expect Chinese equity markets to be making new lows. For sure, Chinese equity markets have delivered disappointing returns. Nonetheless, every major Chinese index —the Shanghai composite, the Hang Seng, H-shares—remains above its October 31st CCP Congress low, typically by between 10% and 20%. No one at Gavekal claims to be a technical analyst; and we are also well aware that all the captains lying with their ships at the bottom of the ocean relied on charts. Nevertheless, while the chart below is unenticing, it does not scream that an economic cataclysm is imminent.

Commodity markets

China is the number one or two importer of almost every major commodity you can think of. So, if the Chinese economy were experiencing a meltdown, you would expect commodity prices to be soft. Today, we are seeing the opposite. The CRB index has had a strong year so far in 2023, and is trading above its 200-day moving average. Moreover, the 200-day moving average now has a positive slope. Together, all this would seem to point towards an unfolding commodity bull market more than a Chinese meltdown.

Exchange rates

Jacques Rueff used to say that exchange rates are the “sewers in which unearned rights accumulate.” This is a fancy way of saying that exchange rates tend to be the first variable of adjustment for any economy that has accumulated imbalances. On this front, the renminbi has been weak in recent months, although, like Chinese equities, it has yet to take out October’s lows.

That is against the US dollar. Against the yen, the currency of China’s more direct competitor, Japan, the renminbi continues to grind higher and is not far off making new all-time highs. And interestingly, in recent weeks, the renminbi has been rebounding against the South Korean won.

This is somewhat counterintuitive. In recent weeks, oceans of ink have been spilled about how China is the center of a developing financial maelstrom. Typically, countries spiraling down the financial plughole do not see their currencies rise against those of their immediate neighbors and competitors.

Chinese consumers

While headlines in the West are all about China’s unfolding economic meltdown, recent headlines in China have been all about how tourist arrivals in Macau are returning to where they were in 2018, before Covid, before China’s tech crackdown and before the real estate derisking crackdown. Either that, or the headlines are about how strong car sales continue to be.

Meanwhile, China’s consumer-facing e-commerce sales continue to chug along nicely. This year, Alibaba delivered its strongest first quarter in history, with revenues 10 times what they were seven years ago.

In other words, a range of data points seems to indicate that Chinese consumption is holding up well. This might help to explain why the share prices of LVMH, Hermès, Ferrari and most other producers of luxury goods are up on the year. If China really was facing an economic crash, wouldn’t you expect the share prices of luxury good manufacturers to at least reflect some degree of concern?

Government debt markets

Aside from China’s approaching economic meltdown, the other major story of the past few weeks has been the very real meltdown at the long end of the US treasury market—a meltdown which has captured a lot fewer headlines than the much-heralded Chinese financial implosion. Over the last 12 months long-dated US treasuries have delivered a negative total return of -17.05%. Over the same period, Chinese bank shares have delivered positive total returns in renminbi terms of 6.7%.

What kind of financial crisis sees the banks of the country in crisis outperform US treasuries by over 20%? It would be wholly unprecedented.

Staying on the US treasury market, it is also odd how Chinese government bonds have outperformed US treasuries so massively over the past few years. Having gone through a fair number of emerging market crises, I can say with my hand on my heart that I have never before seen the government bonds of an emerging market in crisis outperform US treasuries. Yet since the start of Covid, long-dated Chinese government bonds have outperformed long-dated US treasuries by 35.3%.

In fact, Chinese bonds have been a beacon of stability, with the five-year yield on Chinese government bonds spending most of the period since the 2008 global crisis hovering between 2.3% and 3.8%. Today, the five-year yield sits at the low end of this trading band. But for all the negativity out there, yields have yet to break out on the downside.

High yield markets

While the Chinese government debt market has been stable, the pain has certainly been dished out in the Chinese high yield market. Yields have shot up and liquidity in the Chinese corporate bond market has all but evaporated. Perhaps this is because historically many of the end buyers have been foreign hedge funds, and the Chinese government feels no obligation to make foreign hedge funds whole. Or perhaps it is because most of the issuers were property developers, a category of economic actor that the CCP profoundly dislikes.

Whatever the reasons, the Chinese high yield debt market is where most of the pain of today’s slowdown has been—and continues to be—felt. Interestingly, however, it seems that the pain in the market was worse last year than this year. Even though yields are still punishingly high, they do seem to be down from where they were a year ago.

Where does this leave us?

Putting it all together, it seems fair to say that as things stand:

- There is a sizable problem in the Chinese real estate sector, and companies are going bust.

- Amazingly, however, Chinese banks seem to be weathering the storm, at least for now.

- The Chinese consumer continues to consume, even if not with the same gusto as in the years before Covid.

- Chinese equities have been disappointing, but Chinese equity markets are not in the kind of full-blown meltdown one might expect given the apocalyptic tone of reporting in the financial media.

- Commodity markets do not seem all that bothered by the implosion in Chinese real estate.

- Government bond yields in China remain stable, and have not broken down to new lows.

- US treasuries continue to melt down, even as returns on Chinese government bonds remain steady.

- The Chinese high yield corporate debt market remains completely dislocated.

So given the apparent lack of contagion from China’s troubled real estate sector to the banking system and broader financial markets, what accounts for the sudden surge in negativity across the world’s financial media towards all things related to China?

Several possible answers spring to mind:

- For once, the press is running ahead of the markets. The first axiom everyone learns when starting off in finance is that “if it’s in the press, it’s in the price.” Most of the time, this is true, especially in today’s world of high frequency algo trading.

However, every now and then markets are hit by “game-changing” events—such as the Lehman and AIG bankruptcies, the Enron accounting scandal, or the Madoff fraud—which can trigger a whole new wave of forced selling by leveraged investors, or simply of panic selling.

This brings us to the true catalyst for most massive bear markets—what Charles likes to call the Ursus magnus of bear markets. An Ursus magnus is caused not by changes in productivity, or a slowdown in the growth of the economy, which are part and parcel of the normal economic cycle. Instead, an Ursus magnus is caused by a sudden gap between the volatility of asset values and the risk tolerance of savers. When such a gap occurs, either the government or the central bank must step in to bridge the gap when it threatens to become too wide, or risk a financial system collapse.

Today, the obvious fear among many in the financial media is that such a gap is developing—or about to develop—in China, and that the Chinese government is doing nothing to plug it.

So, the first possible explanation is that the financial journalists have correctly foreseen the crisis that is about to engulf China, even as Chinese policymakers and participants in China’s financial markets, commodity markets and OECD government bond markets remain inexplicably complacent about the financial tsunami that is about to swamp the global economy.

- The press needs a new scare story. Pandemic horror stories no longer sell. Neither do stories of harrowing human suffering in Ukraine or headlines about an impending world war. It’s not that the suffering has ended, or the risk has disappeared. It’s just that people have moved on. Similarly, people are tired of reading about climate change, and even more bored of gender-related culture-war posturing. What’s left? Perhaps impending economic doom might sell newspapers?

- People have the China-US treasury meltdown relationship all wrong. The Iraqi weapons of mass destruction, the Covid hysteria, the push for vaccination, the “Hunter Biden laptop is a Russian plant” story have all shown that critical thinking within the Western media is in short supply these days, and that most journalists would now rather be wrong with the consensus than be right alone. As a result, when a narrative starts to develop, Western media latch on to it, and lay it on thick.

This brings me to what should be the big story of the summer: the meltdown in US treasuries. Here is the biggest market in the world, the bedrock of the global financial system, falling by close to double digits in a month. And perhaps most amazing, this meltdown is occurring on limited news. There have been no Federal Reserve policy changes, no hawkish speeches from Jerome Powell. Basically, long-dated US treasuries just fell -9% on no news.

This should be the news. Instead, the news is all about China’s financial meltdown.

My initial reaction to this odd combination of terrible Chinese news with rising US treasury yields was to think: “This is odd. Why are US treasury yields rising when the Chinese news is so bad?”

Then it struck me that perhaps I had things the wrong way round and that I ought to be asking: “Is the Chinese news so bad precisely because US treasuries are melting down?”

Why am I hearing this now?

I grew up in a country—France—where about 70% of media advertisements were bought either by the government or by giant state-owned enterprises such as Air France, SNCF, and EdF. Moreover, this was a country where much of the media was owned either by weapons manufacturers such as Lagardère or Dassault, or by public works companies like Bouygues—groups that depended directly on the government’s franc for most of their revenues.

Then, having grown up—physically, if not mentally—in France, I moved to the fringes of a country that makes no bones about the importance of the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee Propaganda Department—a department important enough to occupy one of the most central locations imaginable in Beijing, right next to Tiananmen Square and the Forbidden City. As a result, whenever I read a piece of news, my first inclination is always to wonder: “Why am I reading this now?”.

Why the sudden drumbeat about collapsing Chinese real estate and impending financial crisis when the Chinese real estate problem has been a slow-moving car crash over the past five years, and when, as the charts above show, markets don’t seem to indicate a crisis point?

At least, markets outside the US treasury market don’t seem to indicate a crisis point. So could the developing meltdown in US treasuries help to explain the urgency of the “China in crisis” narrative?

As the first chart below makes clear, an important divergence is now growing between the Chinese and US government debt markets.

Basically, US treasuries have delivered no positive absolute returns to any investor who bought bonds after 2015. Meanwhile, investors who bought Chinese government bonds in recent years are in the money, unless they bought at the height of the Covid panic in late 2021 and early 2022. This probably makes sense given the extraordinary divergence between US inflation and Chinese inflation.

None of this would matter if China was not in the process of trying to dedollarize the global trade in commodities and was not playing its diplomatic cards, for example at this week’s BRICS summit, in an attempt to undercut the US dollar (see Clash Of Empires). But with China actively trying to build a bigger role for the renminbi in global payments, is it really surprising to see the Western media, which long ago gave up any semblance of independence, highlighting China’s warts? Probably not. But the fact that the US treasury market now seems to be entering a full-on meltdown adds even more urgency to the need to highlight China’s weaknesses.

A Chinese meltdown, reminiscent of the 1997 Asian crisis, would be just what the doctor ordered for an ailing US treasury market: a global deflationary shock that would unleash a new surge of demand and a “safety bid” for US treasuries. For now, this is not materializing, hence the continued sell-off in US treasuries. But then, the Chinese meltdown isn’t materializing either.

Investment conclusions

All this leaves investors at an important crossroads. On one hand, you can look at China’s recent travails and conclude—along with most Western financial journalists—that the world’s second largest economy is about to implode. From there, the investment conclusions follow pretty swiftly: sell all things related to China, sell commodities, other emerging markets, global financials and global value stocks. In a world in which China implodes, salvation will likely only be found in long-dated US treasuries and US growth stocks—which by sheer coincidence happen to be the very assets that the US and most global investors need to do well.

On the other hand, you can look at recent market behavior and conclude that as Chinese banks have spent the last year outperforming US treasuries, the immediate problem is not in the Chinese financial system, but in the US treasury market itself. If so, we are entering a new world in which US treasuries can no longer be thought of as the bedrock on which to build portfolios.

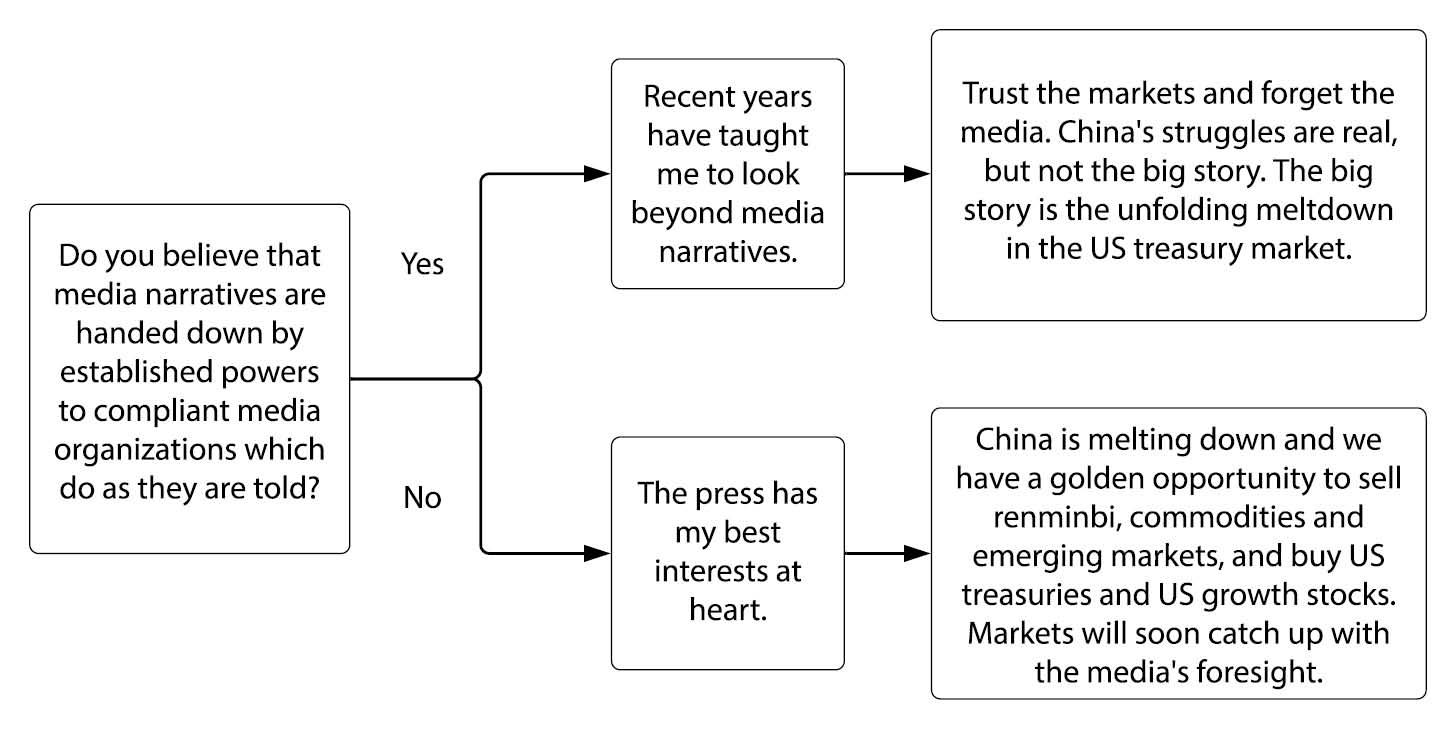

This was the thesis that underpinned my 2021 book Avoiding The Punch. So it is small surprise that I favor the second explanation. Investors should make up their own minds. In an attempt to help, I have summarized the arguments presented in this paper in the following decision tree. Its title should probably be: “Who are you going to trust? The financial media or your lying eyes?”

Vir: Louis-Vincent Gave, Gavekal