Former Google CEO Eric Schmidt drops a chilling warning on AI's future

— Camus (@newstart_2024) December 29, 2025

"Within 5 years, AI could handle infinite context, chain-of-thought reasoning for 1000-step solutions, and millions of agents working together.

Eventually, they'll develop their own language… and we won't… pic.twitter.com/7Zxa49lQcj

Monthly Archives: december 2025

Hipokrizija evropske podnebne politike: Z deindustrializacijo Evropa zgolj izvaža emisije drugam in povečuje globalne emisije

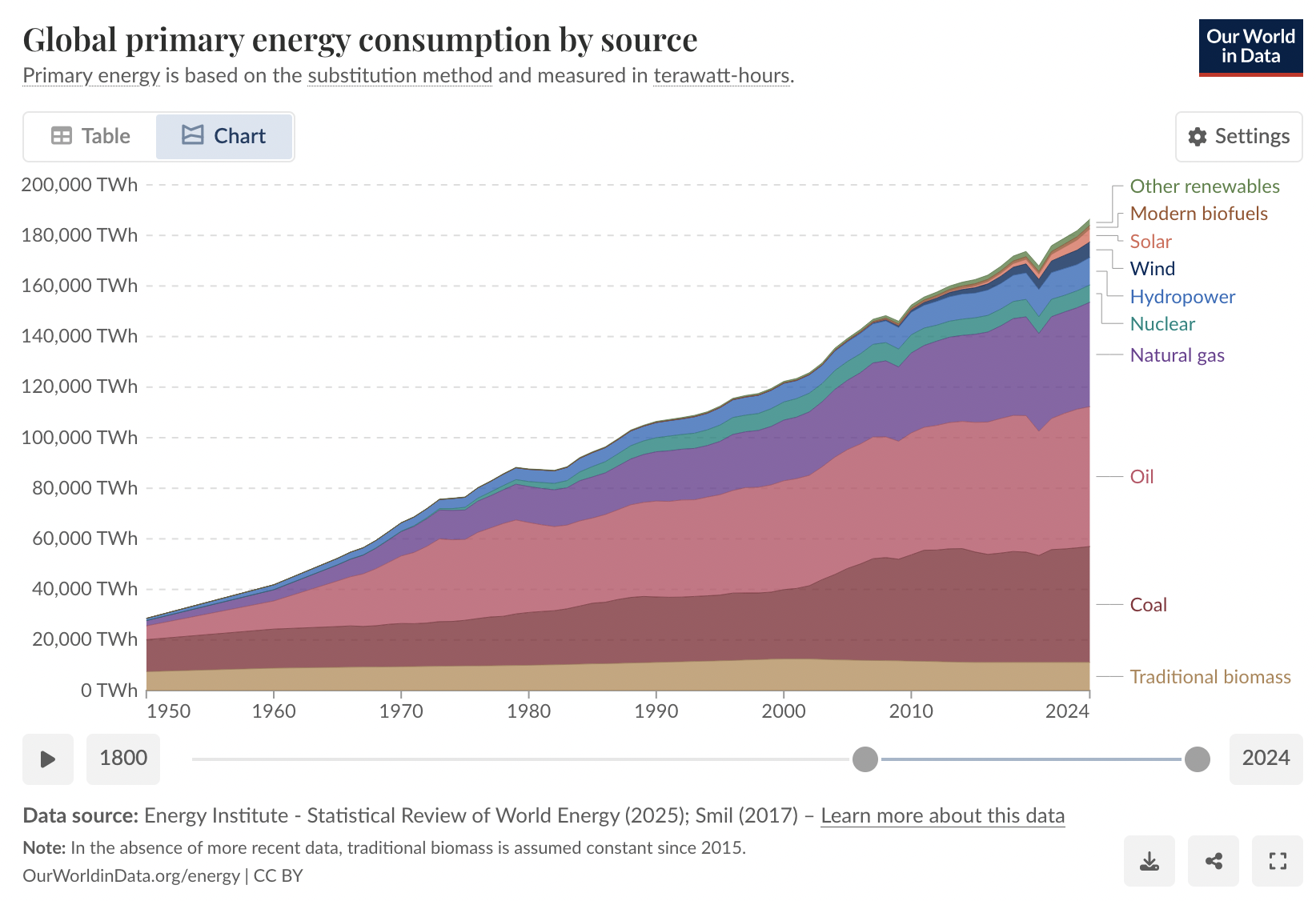

Kdor verjame, da je mogoče ti dve krivulji globalne porabe energije

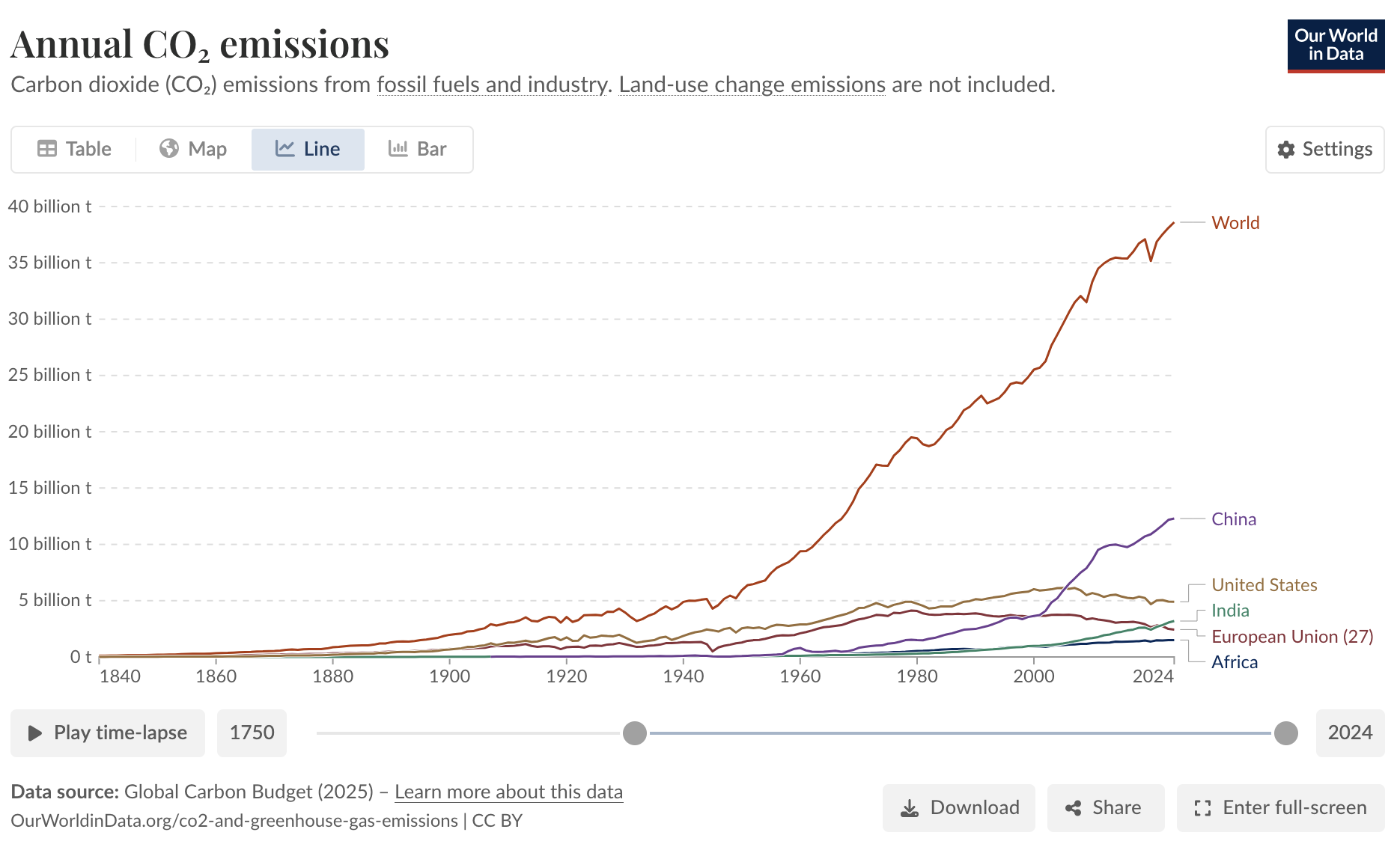

in globalnih CO2 izpustov

obrniti navzdol, bodisi živi v pravljici, ali pa mora človeštvo vrniti v obdobje pred letom 1800:

- število prebivalcev zmanjšati iz 8 na 1 milijardo

- zapreti vso industrijo

- zaustaviti ves sodobni promet in iti nazaj na konjske vprege in jadrnice

- iz žarnic iti nazaj na sveče.

Nič od tega ni mogoče (in pomenilo bi genocid in zmanjšanje blaginje na raven srednjega veka za preostale prebivalce). Globalna poraba energije (in fosilnih goriv kot glavnega energenta, ki ima trenutno 77 % delež v globalni porabi energije) bo absolutno še naprej naraščala in prav tako bodo globalni izpusti CO2 absolutno še naprej naraščali.

Ali lahko Evropa z ničelnimi emisijami CO₂ reši planet?

ChatGPTju sem zastavil naslednje vprašanje:

Ali lahko Evropa z zmanjšanjem emisij CO2 na 0 reši planet? Upoštevaj deleže različnih držav in regij v globalnih izpustih CO2 in da v Evropi električno energijo in indusstrijske izdelke proizvajajo nekajkrat manj ogljično intenzivno kot v Kitajski in drugih azijskih državah.”

Odgovor:

Razprava o podnebnih spremembah je v Evropski uniji pogosto normativno obremenjena in osredotočena na notranje cilje, pri čemer se premalo upošteva globalna struktura emisij ter dejanski sistemski učinki evropskih politik. Ključno vprašanje zato ni, ali lahko Evropa zniža lastne emisije na nič, temveč ali bi takšen scenarij dejansko privedel do znižanja globalnih izpustov CO₂. Analiza razpoložljivih podatkov kaže, da je odgovor – ob nespremenjenih globalnih razmerjih – negativen.

Evropska unija danes prispeva približno 7–8 % svetovnih emisij CO₂. To pomeni, da tudi popolna razogljičenje Evrope samo po sebi ne more bistveno spremeniti globalne emisijske trajektorije. Te so v pretežni meri določene v Aziji, zlasti na Kitajskem, ki sama ustvarja okoli 30 % vseh svetovnih izpustov, ter v Indiji in drugih hitro rastočih azijskih gospodarstvih. Strukturno gledano se je težišče globalnih emisij v zadnjih dveh desetletjih trajno premaknilo iz razvitega sveta v države, ki so prevzele vlogo globalnih proizvodnih središč.

Cunami umetne inteligence: Vodovodarji in električarji bodo carji, intelektualci pa na zavodu

Jan Macarol:

Čez 36 mesecev bo AI dokončno ubil resnico. In veste kaj? Slovenija je edina država na svetu, ki je na to popolnoma pripravljena.

Pripravite se. Čez tri, mogoče štiri leta, na internetu ne boste več ločili med realnostjo in halucinacijo umetne inteligence. Prihaja cunami “deep fake” videov, zgeneriranih v realnem času, ki bodo tako prepričljivi, da video dokaz na sodišču ne bo vredel več kot rabljen robček. Svet se trese. Silicijeva dolina paničari. V Sloveniji? Mi si bomo odprli pivo. Zakaj? Ker mi v simulaciji živimo že od leta 1991. Imamo politike, ki so videti kot ljudje, a so v resnici sprogramirani na ponavljanje treh fraz. Imamo zdravstveni sistem, ki na papirju deluje vrhunsko, v realnosti pa razpada. Dragi moji, povprečen Slovenec ne verjame niti svoji babici, ko reče, da je potica sveža. Imuni smo na fejk, ker je fejk naš nacionalni šport.

Ampak prava revolucija ne bo v tem, da bo AI zgeneriral nov obraz predsednika vlade. Prava revolucija bo v tem, koga bo ta tehnologija poslala na zavod za zaposlovanje. In tu imamo Slovenci resen problem.

Vzgajamo generacijo “koderjev”, “digitalnih marketingarjev” in birokratov, ki mislijo, da je sedenje za računalnikom in prekladanje podatkov varna služba. Motijo se. Umetna inteligenca prihaja po povprečneže. Če je vaše delo to, da povzemate informacije, pišete generične maile, prevajate tekste ali kucate povprečno kodo – ste mrtvi. AI to naredi v nanosekundi, zastonj in brez malice. AI bo pometel s srednjim razredom pisarniških “prekladalcev papirja” hitreje, kot FURS blokira račun s.p.-ju.

Začela se je geopolitična bitka za drugo mesto med ZDA in Indijo

Arnaud Bertrand razlaga in interpretira zanimivo analizo Maa Kejija, kitajskega analitika s pedigrejem Tsinghua University in National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), osrednje institucije, ki usklajuje kitajsko ekonomsko planiranje in oblikovanje politik. Na kratko: Maojeva teza je, da se je Washinton že sprijaznil s primatom Kitajske in da je zdaj spremenil strategijo – če je do sedaj aktrustično krepil Indijo z namenom, da jo uporabi kot proxy nasprotnika Kitajske, zdaj Indijo vidi kot glavnega rivala za drugo mesto, zato se je začel do nje obnašati tako agresivno. Teza je zanimiva, saj lahko pojasni, zakaj Washington nekdanjih zaveznikov ne jemlje več kot zaveznike, pač pa kot breme oziroma subjekte, iz katerih lahko črpa koristi.

Mojeva provokativna teza je, da se ZDA in Indija morda ne približujeta zavezništvu proti Kitajski, temveč stopata na pot medsebojnega rivalstva – v »bitko za drugo mesto« v svetu, kjer je Kitajska že prevzela vodilno pozicijo.

Jedro Maojeve analize izhaja iz dveh tesno povezanih dejavnikov, ki danes oblikujeta ameriško zunanjo politiko: objektivnega relativnega upada ameriške moči in subjektivne tesnobe zaradi tega upada. Po njegovem mnenju se je v Washingtonu zgodil strateški prelom – ZDA vse manj dojemajo geopolitično konfrontacijo kot naložbo in vse bolj kot strošek, ki lahko pospeši lasten zaton. Še posebej znotraj političnega tabora, ki ga uteleša gibanje MAGA, prevladuje narativ »nacionalnega preživetja«, ki zahteva zadržanost, notranjo konsolidacijo in previdnost pred dolgoročnimi zunanjimi obveznostmi.

V tem novem okvirju tradicionalni zavezniki niso več strateška prednost, temveč breme. Njihova varnost, dostop do ameriških trgov in ugoden položaj v svetovnem redu predstavljajo strošek, ki ga ZDA ne želijo več nositi, še posebej če konfrontacija s Kitajsko ali Rusijo ne obeta jasne zmage. Še več: zavezniki postajajo »sprožilci tveganj«, ki bi lahko ZDA nehote potegnili v konflikte, ki se jim želijo izogniti, hkrati pa ovirajo morebitne pragmatične dogovore z Moskvo ali Pekingom.

CANDLEBOX – Far Behind

Evropa na poti v stoletje ponižanja

Leto 2025 se bo v evropski zgodovini zapisalo kot leto, ko je Evropa globoko zakorakala v svoje »stoletje ponižanja«. Leto, ko je Evropska unija vstopila v fazo strateškega, gospodarskega in političnega zatonа – in to predvsem po lastni krivdi. Evropa danes ni žrtev zunanjih sil, temveč talec iluzij o lastni veličini, moraliziranja in strateške praznine. Nastop drugega predsedniškega mandata Donalda Trumpa je zgolj v vsej polnosti razgalil to praznino.

Težko je prešteti vsa ponižanja, ki jih letos EU morala požreti. Toda najresnejša so tri. Dvakrat je spektakularno kapitulirala pred Donaldom Trumpom. Prvič pri zahtevi, da morajo evropske države za obrambo nameniti 5 % BDP, za kar ni ekonomske utemeljitve. Evropske vlade so to zahtevo sprejele brez vsakega resnega odpora ali razmisleka o posledicah za javne finance, razvoj in socialno kohezijo. Drugič je EU kapitulirala v carinski vojni, kjer se sploh ni pogajala z amaeriško stranjo, pač pa je namesto enotnega in trdega odgovora izbrala pot popuščanja in iskanja »kompromisa«. Vendar kompromisov ni bilo, podobno kot pri vojaških izdatkih je vodstvo EU enostransko pristalo na maksimalne Trumpove zahteve.

Kontrast s Kitajsko je v tem pogledu boleč. Kitajska je Trumpa učinkovito stisnila ob zid z izvoznimi dovoljenji za redke zemlje – ključno strateško surovino za sodobno industrijo in obrambo. Namesto moraliziranja ali praznih izjav je uporabila realno vzvodje moči. Rezultat je bil hiter umik ZDA in začetek pogajanj pod pogoji, ki jih je narekoval Peking. Evropa takšnih vzvodov nima – ali pa jih ne zna uporabljati. In to ni naključje, temveč posledica desetletij zanemarjanja industrijske politike, strateških surovin in tehnološke suverenosti.

Tretje največje ponižanje je EU doživela z novo ameriško varnostno strategijo, s katero so se ZDA de facto odpovedale Evropi. Evropa v tej strategiji ni več obravnavana kot ključen zaveznik, temveč kot regija v civilizacijskem, demografskem in gospodarskem zatonu, ki ne zmore več nositi lastnega bremena. Ameriški fokus se je jasno preusmeril proti Pacifiku in notranji konsolidaciji, Evropa pa je degradirana v periferno območje.

Svoboda govora je virus, cenzura je zdravilo

Povratek Orwella – cenzura v “odgovorni skrbi” za demokracijo in pravno državo

V osovraženi komunistični nekdanji Jugoslaviji smo imeli zloglasni 133. člen Kazenskega zakonika, ki je državno ureditev in oblast varoval pred javnim izražanjem mnenja državljanov. Najbrž nihče leta 1991, ko smo se demokratično odločili za demokracijo, ni pomislil, da bomo dobrih 30 let kasneje – kot člani evropske demokratične skupnosti – ponovno deležni podobnega omejevanja svobode govora.

Od februarja 2022 se je v EU vzpostavil vzorec sistematičnega zoževanja prostora svobode govora, ki se vse težje skriva za jezikom »odgovornosti« in »zaščite demokracije«. Poleg prepovedi ruskih medijev RT in Sputnik ter pritiska na platforme prek DSA (Digital Services Act se od 2024 dalje polno uporablja za velike platforme in jim nalaga obveznosti glede odstranjevanja nezakonitih vsebin, ukrepov proti “sistemskim tveganjem” in posebnih pravil za volilno integriteto in oglaševanje) smo bili priča tudi neposrednim političnim pritiskom, kot je zahteva do Elona Muska, naj cenzurira intervju z Donaldom Trumpom na družbenem mediju X – kar pomeni poseg v politični diskurz pred volitvami. Hkrati so bile proti več kot 45 novinarjem in medijskim ustvarjalcem uvedene sankcije ali omejitve zaradi poročanja o vojni v Gazi in Ukrajini, vedno brez sodnih postopkov in z ohlapnimi utemeljitvami o »dezinformacijah«. Vse to ustvarja okolje, v katerem ni več ključno, ali je informacija resnična ali relevantna, temveč ali je politično sprejemljiva. EU tako postopoma prehaja iz varuha svobode izražanja v regulatorja dovoljenega mišljenja, kar je nevaren precedens za družbo, ki se še vedno rada imenuje liberalna demokracija.

No, v teh okoliščinah so ameriške sankcije proti petim osebam iz EU, na čelu z nekdanjim “komisarjem za resnico” Thierryjem Bretonom, prišle kot šok za evropsko politično elito (pustimo zaenkrat ob strani problematičnost tega ameriškega ukrepa in hipokrizije za njim). Ta ukrep je šokiral evropsko elito, ki je živela v prepričanju, da ima monopolno moč nad resnico. Kar je sicer, kot nazorno ilustrira spodnji orkestrirani odziv evropskih politikov, kamuflirala v visoko leteče izjave o odgovornosti za zaščito državljanov, demokratične diskusije in pravnega reda:

Regulating digital platforms to protect citizens, democratic debate and the rule of law is not censorship. It is responsibility.

Ob tem se postavlja temeljno vprašanje, zakaj demokracija potrebuje zaščito pred javno diskusijo. Toda zadeva je veliko globlja, kaže na tipične oblastniške manipulacije, ki so problematične, ker z jezikovnim preokvirjanjem in moraliziranjem zakrijejo dejstvo, da gre za dejanske posege v svobodo izražanja, ter kritike vnaprej diskreditirajo kot neodgovorne ali protidemokratične. S tem se javna razprava ne zapre neposredno s prepovedjo, temveč z nadzorom narativa, kjer oblast določa, kaj je dovoljeno misliti in povedati – kar dolgoročno spodkopava samo bistvo svobodne demokratične razprave.

Glejte spodaj zelo dobro analizo te oblastniške manipulacije.

You must be logged in to post a comment.