Vem, da je o tem blasfemično že razmišljati, kaj šele govoriti. Toda objektivna, racionalna analiza kaže, da se je pot navzdol in začetek trenda relativnega zaostajanja EU začel aredi 1990-ih let – z začetkom poglobljene integracije. Do takrat je bila EU (tedaj Evropska gospodarska skupnost – EGS) dejansko zgolj prosto carinsko območje z nekaj koordinacije na področju monetarne politike (mehanizem ERM 1 glede koordinacije medsebojnih valutnih tečajev). Leta 1993 je bil lansiran Skupni trg (European Single Market) (mimogrede, na to temo sem takrat naredil svoj prvi ekonomski model za simulacijo učinkov skupnega trga) z ambicijo prek skupnih evropskih politik doseči 4 svobode (prost pretok blaga, storitev, kapitala in ljudi), leta 1999 pa evropska monetarna unija (EMU).

To so bile nobel iniciative, ki se še danes zdijo izjemne v svojem cilju – oblikovati enotno evropsko gospodarstvo s podrtjem vseh fizičnih in administrativnih meja s končnim ciljem oblikovati Združene države Evrope po ameriškem zgledu. Evropa naj bi s to poglobitvijo integracije postala močnejša in v končni instanci najmočnejše gospodarstvo na svetu.

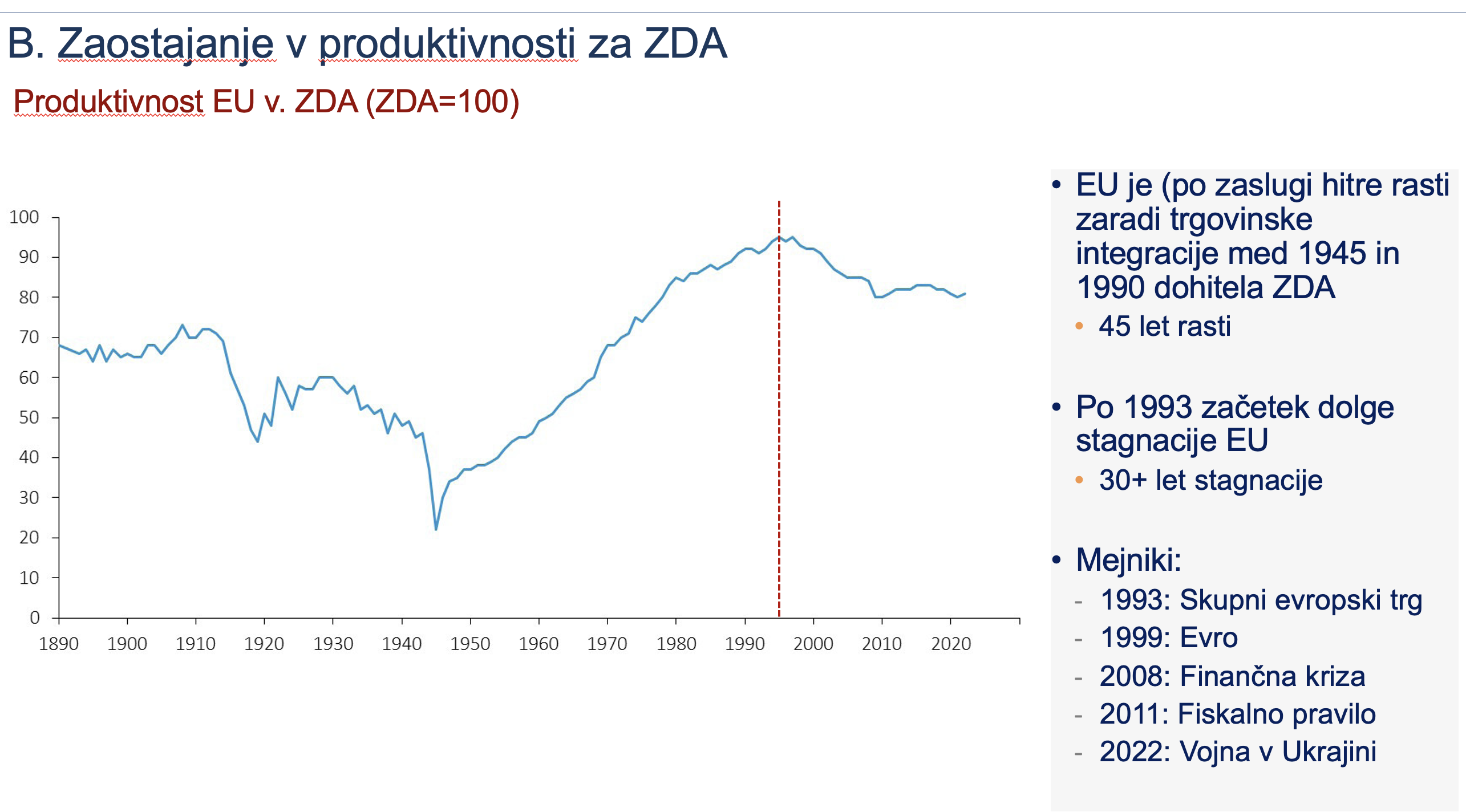

Problem ambiciozne iniciative pa je v tem – da je z vsako novo skupno politiko (od kapitalske direktive, energetske politike, politike konkurence, politike državnih pomoči, …, do monetarne politike in fiskalnega pakta) EU postajala šibkejša in ne močnejša. Te skupne politike so začele dušiti gospodarstva posameznih članic, ki so postajala manj, in ne bolj, konkurenčna. In evropski gospodarski vlak se je usmeril navzdol. Poglejte spodnjo sliko.

Paradoks poglabljanja integracije EU je, da Evropo duši, namesto, da bi jo krepila. Duši gospodarski razvoj posameznih članic EU. Trije primeri. Prvič, skupna politika državnih pomoči je namenjena temu, da ne bi kakšno podjetje iz katerekoli članice dobilo “nelojalne prednosti” prek državnih subvencij. Torej da ne bi neko nemško podjetje z državno spodbudo dobilo prednosti pred francoskimi in obratno. Toda posledica tega, da Komisija v imenu držav preprečuje, da bi katerokoli podjetje dobilo prednost, je, da v Evropi nobeno tehnološko podjetje ne more zrasti. Za razliko od tega kitajska in ameriška podjetja s pomočjo državnih pomoči vznikajo in se razvijajo v tehnološke velikane. V EU pa imamo gospodarske dinozavre, ustanovljene pred ali malce po drugi svetovni vojni.

Drugič, skupna energetska politika naj bi omogočila, da bi vsa evropska gospodinjstva in podjetja bila deležna najnižjih cen na trgu. V resnici pa zaradi različnih energetskih konceptov po posameznih državah vodi k temu, da smo vsi deležni najvišjih in ne najnižjih cen energije na trgu, kar ubija konkurenčnost in vodi v energetsko revščino. Denimo Francija ima jedrske elektrarne in lahko svojim subjektom načeloma ponuja elektriko po ceni izpod 50 evrov za megavatno uro. Vendar tega ne sme in ne more, ker Nemčija vodi politiko prehoda na nestanovitne obnovljive vire z zaprtjem poceni jedrskih elektrarn, subvencioniranjem vetrnic, sončnic in biomase ter kurjenjem premoga in plina za proizvodnjo nadomestne energije. Posledično se zaradi skupne energetske politike cene elektrike v EU oblikujejo na osnovi najdražje (mejne) elektrarne. In to so običajno plinske ali premogovne zaradi visokih dajatev za CO2. Torej na koncu so vsi Evropejci, ne glede na lastne energetske sposobnosti, deležni najvišjih cen elektrike v Evropi, namesto lastnih nacionalnih cen.

Tretjič, evro je dokončno ubil razvojni potencial EU. Z vzpostavitvijo enotne valute in skupne centralne banke je bila ukinjena fleksibilnost in sposobnost ukrepanja nacionalnih držav v primeru asimetričnih šokov (ali simetričnih šokov z asimetričnimi učinki), ki zdaj ne morejo svojemu gospodarstvu v krizi pomagati z devalvacijo valute ali znižaanjem obrestne mere in dodaatno likvidnostno pomočjo, ker to počne ECB v Frankfurtu s politiko “one size fits all”. Dodatno k temu je Nemčija zahtevala strogo koordinacijo fiskalnih politik, zaradi česar posamezne države ne smejo pomagati svojemu gospodarstvu, sicer kršijo pravila glede deficita. In to pomeni, da brez pomoči države potrebujejo dolga leta, da se z interno devalvacijo (znižanjem svojih plač glede na druge države) izvlečejo iz krize. S čimer vedno bolj zaostajajo za drugimi. In seveda tudi EU kot agregat.

Podobno je pri ostalih politikah. Torej s skupnimi politikami (pravli) si v Evropi jemljemo fleksibilnost v odzivanju na krize in pri razvojnih politikah in omejujemo eden drugega, da nihče ne more zrasti. Posledično vsi skupaj tonemo. Medtem ko drugi rastejo in se čudijo naši norosti.

O tem bom še pisal, ker menim, da je to ključni problem EU, ki se ga ne da rešiti z “več Evrope”, z še več administriranja. Pač pa samo z “manj Evrope” oziroma povratkom EU nazaj v institucionalno stanje pred letom 1993 – nazaj v prostocarinsko območje s koordinacijo valutnih tečajev in nacionalnimi ekonomskimi in drugimi politikami.

Spodaj je nekaj odlomkov na to temo, ki jih je napisal prodorni in progresivni (levi) politolog Thomas Fazi (sicer avtor knjige “Reclaiming the State”). Na to temo sem imel nekaj predavanj in vidim, da Fazi razmišlja v isto smer.

This is part two (part one is available here) of a study I’ve been working on for a while. It provides a comprehensive critique of the EU’s supranational model of integration, analysing its structural, economic and geopolitical shortcomings. It highlights the way in which EU and the single currency, far from making Europe stronger, more competitive and more resilient, have paved the way for economic crisis and stagnation, worsened economic disparities, and contributed to loss of competitiveness, geopolitical marginalisation and democratic decay.

Crucially, the study argues that failure of the EU project isn’t rooted in a lack of integration — and definitely cannot be solved by resorting to “more Europe” — but rather lies in supranational integration itself. It concludes that the EU’s structural deficiencies are irreparable within the confines of its existing model and questions the viability of supranationalism as a viable governance approach in a multipolar and state-driven global order.

In part one I analysed the empirical data on the EU’s economic integration, which shows a stagnation or decline in economic performance post-integration compared to the pre-integration trend. It highlighted how the Single Market failed to boost intra-EU trade or GDP growth; how the eurozone underperformed relative to non-euro EU members and other advanced economies; and how divergence in economic outcomes among member states intensified, contradicting promises of convergence.

…

The dysfunctional nature of the euro has been extensively analysed. Nevertheless, revisiting some of the key arguments remains essential — especially since the continued existence of the single currency is now widely accepted, even by European populists, as an unavoidable reality, despite its persistent role as a significant impediment to economic growth. In short, the euro remains a subject we must address, however uncomfortable the discussion may be.

Under normal circumstances, a state has several economic policy tools at its disposal, including monetary policy, exchange rate policy and fiscal policy. However, with the introduction of the euro, the management of the first two was centralised at the European level, while the third became constrained by stringent austerity criteria. As a result, countries that joined the single currency effectively forfeited a substantial degree of economic sovereignty in a single stroke.

This loss is particularly significant given that fiscal policy — which encompasses industrial strategy, employment measures and welfare initiatives — is intrinsically linked to control over monetary and exchange rate policy. Without the ability to issue its own currency, a country loses a crucial mechanism for managing economic policy effectively, both in addressing demand-side challenges, such as ensuring societal welfare and employment, as well as supply-side ones, such as sustaining industry and output.

The core issue is that this surrender of sovereignty was only minimally offset by compensatory mechanisms at the European level. The euro operates as a stateless currency, and the absence of instruments to adjust national economies was not adequately balanced by robust intra-European fiscal transfers or the establishment of a sufficiently large European federal budget. The EU’s budget, amounting to a mere 1 percent of EU GDP — compared to a federal budget of over 20 percent in the US — is distributed across a wide range of spending programs, leaving limited capacity to fund large-scale projects or new strategic priorities. In sum, the single currency severely limited the member states’ individual capacity for investment without offering effective alternatives. This structural limitation is a key reason why public sector investment in the EU has consistently lagged behind that of the United States and other advanced economies.

The euro was constructed in direct contradiction to established economic principles on how to design a monetary union. Its flawed architecture became glaringly evident during the financial crisis of 2007-2008. Ordinarily, countries respond to external economic shocks by allowing their exchange rates to depreciate, which helps absorb the impact. Furthermore, by shortening the duration of economic distress following a shock, exchange rate adjustments can help prevent prolonged recessions, which, as research has highlighted, can erode long-term growth potential. This option, however, was unavailable to the countries of the eurozone.

Moreover, when the financial crisis struck, member states found themselves vulnerable because they lacked the ability to issue currency to purchase their own bonds and thereby control interest rates. Additionally, the ECB’s unwillingness to act as a lender of last resort left them defenseless against market speculators, or “bond vigilantes”, which drove bond yields (interest rates) to soar in several countries, particularly those in the so-called periphery — Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain, often disparagingly referred to as the “PIIGS”. This situation triggered the European sovereign debt crisis, also known as the euro crisis.

For nearly three years — from late 2009 to mid-2012 — the ECB refrained from intervening meaningfully to support government bond markets in the euro area. As a result, member states were left at the mercy of financial speculation and forced to implement severe austerity measures to meet escalating interest payments. In some cases, such as in Ireland, Portugal, Greece and Spain, these countries were compelled to seek financial assistance from the so-called “troika” — a tripartite body composed of representatives from the European Commission, the ECB, and the International Monetary Fund — in exchange for even more stringent austerity conditions. These countries effectively found themselves under a form of “controlled administration”.

This was presented in the mainstream media and by policymakers as a “natural” consequence of the fact that the countries in question had accrued excessive debt levels, which had caused them to “lose the confidence of investors”. In fact, there was nothing natural about it. As we will see, to the extent that eurozone countries were (and continue to be) subject to the “market discipline” of bond vigilantes — and to the risk of national default/insolvency — this was (and still is) uniquely a consequence of the defective architecture of the eurozone, further exacerbated the actions of EU institutions.

Vir: Thomas Fazi

You must be logged in to post a comment.