Ne pravim, da se povsem strinjam s člankom Yun Suna v Foreign Affairs, ima pa zelo dobre, logične poante. Kajti Kitajski res ni treba narediti nič, samo počakati mora, da Trump postopno razgradi ameriško globalno moč in njen položaj v svetu, v vmesnem času pa Kitajska nadaljuje s krepitvijo svoje tehnološke in gospodarske prednosti ter krepitvijo odnosov z državami izven OECD z več kot 6.7 milijard prebivalcev (82 % svetovnega prebivalstva). To je v skladu s krilatico, ki jo pripisujejo Napoleonu Bonaparteju: Ne moti nasprotnika, ko dela napake.

Kitajska je svojo “Trumpovo strategijo” zastavila že v prvem Trumpovem mandatu in preusmerila precejšen delež svojega neposrednega izvoza v ZDA posredno preko ASEAN držav (predvsem Vietnama) in Mehike. Spodnja slika kaže, da se je delež ZDA v kitajskem izvozu med 2018 in 2024 zmanjšal iz 19 % na dobrih 14 %, medtem ko se je delež izvoza v države ASEAN + Mehiko povečal iz 14 na 18 %…

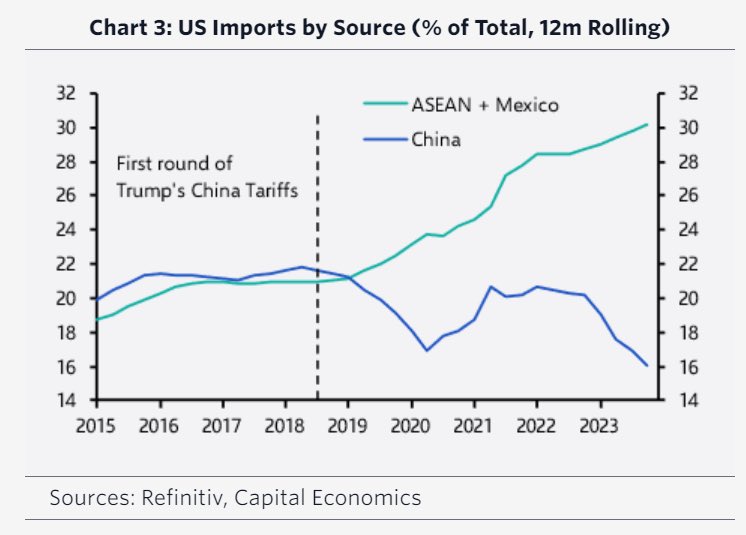

.. hkrati pa se je delež držav ASEAN + Mehike v ameriškem uvozu povečal iz 20 % na dobrih 30 %.

.. hkrati pa se je delež držav ASEAN + Mehike v ameriškem uvozu povečal iz 20 % na dobrih 30 %.

Kitajska ve, kaj dela. Diverzificira svoj izvoz in danes njen izvoz v ne-OECD države že presega izvoz v OECD države. Trumpove carine bodo sicer v določeni meri prizadele kitajski izvoz, toda ta udarec je obvladljiv.

Trump je izvrstna priložnost tudi za Evropo, da končno odraste in se osamosvoji od ZDA: politično, vojaško in tehnološko. Hkrati bi morale države EU kot strateško alternativo poglobiti gospodarske odnose s Kitajsko, pa tudi z Rusijo (zaradi energentov in ključnih surovin za evropsko industrijo).

__________

Beijing has been expecting the Trump administration to pursue tough policies toward China, potentially escalating the two countries’ trade war, tech war, and confrontation over Taiwan. The prevailing wisdom is that China must prepare for storms ahead in its dealings with the United States.

Trump’s imposition of ten percent tariffs on all Chinese goods this week seemed to justify those worries. China retaliated swiftly, announcing its own tariffs on certain U.S. goods, as well as restrictions on exports of critical minerals and an antimonopoly investigation into the U.S.-based company Google. But even though Beijing has such tools at its disposal, its ability to outmaneuver Washington in a tit-for-tat exchange is limited by the United States’ relative power and large trade deficit with China. Chinese policymakers, aware of the problem, have been planning more than trade war tactics. Since Trump’s first term, they have been adapting their approach to the United States, and they have spent the past three months further developing their strategy to anticipate, counter, and minimize the damage of Trump’s volatile policymaking. As a result of that planning, a broad effort to shore up China’s domestic economy and foreign relations has been quietly underway.

China’s preparations roughly mirror the Biden administration’s China strategy of “invest, align, and compete,” which involved investing in U.S. strength, aligning with partners, and competing where necessary. Beijing’s playbook for riding out the Trump years, meanwhile, focuses on making the domestic economy more resilient, reconciling with key neighbors, and deepening relationships in the global South. Trump may well be able to score some short-term victories, but Beijing’s plans look beyond him. Chinese leaders remain convinced of the country’s historic destiny to rise and displace the United States as the world’s preeminent power. They think that Trump’s policies will undermine U.S. power and reduce U.S. global standing in the long run. And when that happens, China wants to be ready to take advantage.

…

China is also looking to diversify its trade options. Over the past few months, statements from the Chinese foreign and commerce ministries have referred repeatedly to China’s effort to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, the 12-member trade agreement that succeeded the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which stalled in 2017 after the United States withdrew. Members of the CPTPP must meet stringent entry requirements, which in China’s case would require serious structural reform. Beijing recognizes the value of multilateral trade mechanisms: China’s accession into the World Trade Organization in 2001 was probably the single largest factor in China’s economic rise. As countries move away from the WTO and toward alternative arrangements such as the CPTPP, Beijing wants to make sure it is not left out. With Trump in power, inclusion is all the more vital as China seeks to compensate for lost access to U.S. markets.

…

China has also been expanding its cooperation with countries in the global South that offer backdoor access to U.S. markets. As tariffs and supply-chain disruptions break direct trade links between the United States and China, more and more trade happens indirectly. In effect, the same Chinese materials and parts are used in goods exported to the United States—but now the final products are manufactured or assembled in countries other than China. Beijing has accepted this transition to backdoor trade; China’s exports are still strong, with the country’s trade surplus reaching a peak of almost $1 trillion in 2024. Its fastest growing export markets are countries in the global South, including Brazil, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam, many of which are acting as middlemen by processing Chinese materials and exporting the finished goods to the United States.

Over the past few years, China has deliberately facilitated growth in these supply networks through investment in Asia and Latin America. Chinese investment in Vietnam, for example, increased by 80 percent in 2023 to $4.5 billion, and Chinese-Vietnamese bilateral trade reached $260 billion—more than China’s trade with Russia, even with all the oil and gas China has purchased from Russia during the war in Ukraine. In Mexico, according to Xu Qiyuan, a senior economist at the China Academy of Social Sciences, China’s outbound direct investment in 2023 reached as high as $3 billion, ten times more than what the official data reports. Where countries can offer routes into the U.S. market, Chinese companies have been eager to invest.

Although China would still prefer to trade directly with the United States, leading a parallel trading system with the global South is an acceptable alternative for Beijing. There is a chance Trump could decide to punish third-party countries for their economic cooperation with China, as he has threatened in the case of Panama. Beijing does not have an obvious, easy solution to this type of disruption. But Trump’s moves may not necessarily harm China’s economic relationships, either—for countries on the receiving end of his ire, practical economic considerations could still prevail. Indeed, after Italy withdrew from China’s Belt and Road Initiative in December 2023, its economic ties to China did not disappear—bilateral trade increased in 2024. For many countries in the global South, lucrative economic deals with China will still have strong appeal. Beijing, furthermore, could reap the benefits if heavy-handed U.S. measures undermine Washington’s relations with key countries.

…

Yet Chinese leaders remain confident that, even if the country’s economy suffers, four years of Trump is unlikely to send it into a full-blown crisis. And they anticipate that if Trump follows through on his declared policies, such as those on trade and territorial expansion, he could do severe damage to the United States’ credibility and global leadership. Beijing thus sees Trump’s second term as a potential opportunity for China to expand its influence farther and faster. In this view, competition with the United States is not in itself the driving force behind China’s grand strategy. It is instead one component of a larger process: China’s rise and displacement of the United States as the world’s leading superpower, what Xi often describes as “changes unseen in a century.” Beijing assumes that Washington’s own policies will dismantle the foundations of U.S. global hegemony, even if it creates a lot of turbulence for other countries in the process. China’s top priority, then, is simply to weather the storm.

Vir: Yun Sun, Foreign Affairs

You must be logged in to post a comment.