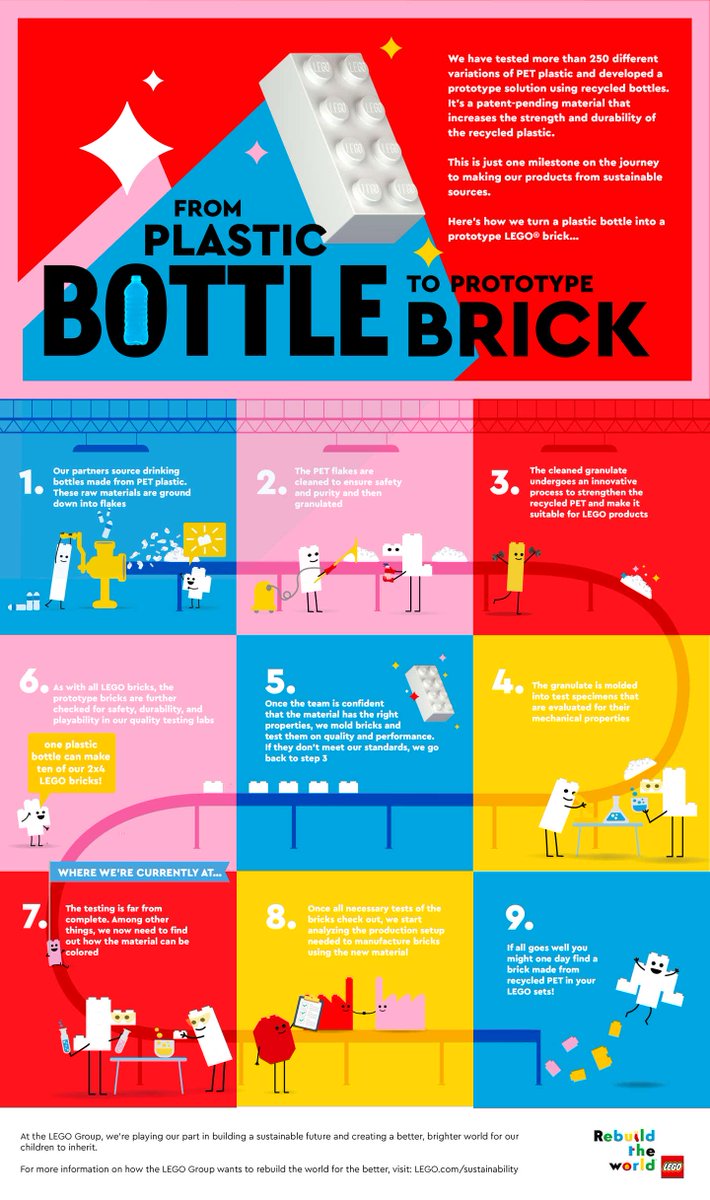

Zanimiva zgodba v spodnji niti o tem, kako težko se bo znebiti nafte in drugih fosilnih materialov pri proizvodnji materialov, ki jih uporabljamo vsak dan. Primer lego kock: najbrž niste vedeli, da sta za en kilogram “plastike” (ABS), ki se uporablja za proizvodnjo lego kock, potrebna 2 kilograma nafte. Razvojniki pri LEGO se že dolga leta trudijo, da bi našli “zeleno” alternativo za ABS, denimo reciklirane plastenke. Poskušali so z desetinami različnih materialov, vendar jim nikakor ne uspe doseči ustrezne kvalitete materiala (trdnosti). Najbolj ironično pa je, da imajo vsi alternativni materiali, ki so jih testirali, bistveno večji ogljični odtis od nafte in da so tudi ustrezno dražji od nafte.

Podobno velja za druge praktične uporabe fosilnih goriv. Denimo: zeleni ideologi nas na polno prepričujejo, da je vodik “sveti gral” energetskega prehoda iz fosilnih goriv na obnovljive vire. Vodik naj bi se uporabljal kot hranilec energije: dnevne viške energije iz sončnih elektrarn naj bi prek elektrolizerjev pretvarjali v vodik, ta vodik shranjevali za čas kurilne sezone in ga uporabljali namesto plina za proizvodnjo električne energije v jesensko-zimskem času, ko ni sonca. Problem tega energetskega svetega grala je podoben tistemu svetopisemskemu svetemu gralu – je zgolj mit, je utvara, je samoprevara. Problem vodika kot hranilca energije je namreč najmanj dvojen: (1) je izjemno porozen plin in ga je je izjemno težko (in drago) skladiščiti (še najlažje v solnih kavernah, ki pa so zgolj na severu Evrope), in (2) proizvodnja vodika prek elektrolize vode iz sončnih panelov je božjastno draga.

V naših geografskih razmerah, kjer sonce sije 12.5 % časa letno, in ob cenah tehnologije, kot naj bi veljale sredi 2030-ih let (predvidevanja IEA), bi en kilogram vodika iz dnevnih viškov elektrike iz sonca (ob 12.5 % izkoriščenosti elektrolizerjev in sedanjih cenah elektrike iz sonca) stal okrog 17 evrov. Če to preračunate v megavatne ure, bi 1 MWh vodika (brez davščin) stala 425 evrov. Za primerjavo: 1 MWh dizla (brez davščin) stane okrog 75 evrov. Če bi imeli posebne sončne elektrarne s priključenimi baterijami in na ta način stopnjo izkoriščenosti elektrolizeerjev dvigniti iz 12.5 na 30 %, bi se proizvodna cena vodika do leta 2040 lahko spustila na okrog 6 evrov za kilogram. To pomeni, da bi proizvodna cena 1 MWh vodika (brez davščin) stala okrog 150 evrov, kar je dvakrat dražje od dizla brez davščin. Drugače rečeno, vodik bi moral biti neobdavčen in njegovo proizvodnjo bi morali subvencionirati z okrog 75 evrov za MWh. In seveda bi morali najti norce med investitorji, ki bi bili pripravljeni investirati v proizvodnjo, ki deluje samo 30 % časa.

Torej vodik ne bo sveti gral zelenega energetskega prehoda. Najbolj ironično je, da se danes 99.9 % vodika proizvede iz fosilnih goriv (z elektrolizo pa le 0.04 %; podatki IEA, Global Hydrogen Review), da proizvodna cena vodika na podlagi metanacije zemeljskega plina stane manj kot 2 dolarja za kilogram. Proizvodnja vodika bi bila ekonomična zgolj, če bi ga proizvajali iz že amortiziranih jedrskih elektrarn (izjemno nizka cena elektrike in visok faktor izkoriščenosti elektrolizerjev) – proizvodna cena bi znašala okrog 2 evra za kilogram (iz novih jedrskih elektran pa med 2.5 in 3 evri za kilogram). Toda zakaj bi proizvajali vodik iz poceni elektrike iz jedrskih elektrarn, ga shranjevali (še ne vemo kje) in ga nato kurili v plinskih elektrarnah za proizvodnjo elektrike in v tem procesu pretvorb izgubili še za več kot 50 % energije?!

IEA je pokazala, da bi bila proizvodnja elektrike iz vodika izjemno draga: če bi bil vodik ektremno poceni (1.5 $/kg), bi 1 MWh elektrike stal več kot 150 $, pri ceni vodika 3 $/kg, bi 1 MWh elektrike stal okrog 270 $. Toda vodika iz viškov sončne energije ni mogoče proizvesti po tej ceni, cena elektrike iz amortiziranih jedrskih in hidro elektrarn danes znaša med 25 in 30 evri za MWh in cena elektrike iz jedrske elektrarne, ki bi jo zgradili danes, bi povprečno v 60 letih obratovanja stala manj kot 50 evrov za MWh (okrog 70 EUR/MWh v prvih 30 letih in 26 EUR/MWh v naslednjih 30 letih obratovanja.

Torej hudič bo najti alternative za fosilna goriva (denimo za proizvodnjo umetnih gnojil in plastične mase), težko jih bo najti za transport, medtem ko je v proizvodnji električne energije to dokaj trivialno – jedrska in hidro energija sta skoraj povsem brezogljični (bistveno (8 do 10-krat) bolj od elektrike iz sončnih elektrarn) in ekstremno poceni glede na alternative, hkrati pa stanovitna in stabilna vira energije (sploh jedrska).

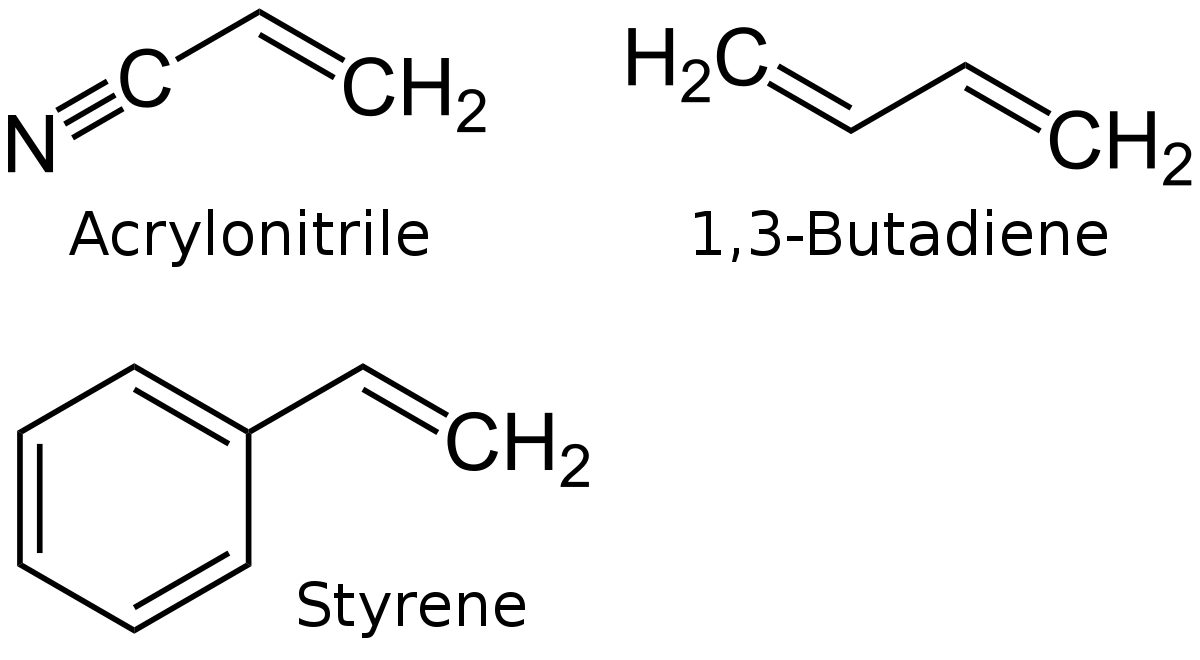

Standard Lego bricks are made of something called Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene.

ABS is a tough thermoplastic you often find in the handles of scissors or the frames of hard carry-on baggage cases.

But Lego bricks are prob the most iconic application.It’s worth saying btw not all Lego pieces are made out of ABS.

Baseplates are moulded from high impact polystyrene. Gearwheels are polyamide.

The small, flexible green pieces that look like plant stalks or flags are polyethylene, and so on and so on.

lego.com/en-us/sustaina…But the vast majority of Lego – more than 80 per cent – is those bricks you’ve doubtless played with and/or found yourself cursing as you accidentally step on top of them. And these ones?

They’re all made from ABS. Why?It’s incredibly durable. It can be moulded incredibly precisely, with tolerances of within four microns, meaning one brick fits neatly into another.

And it has unbeatable “clutch power”: the bricks stick together robustly but are also easy to pull apart.Its deployment in the 1960s was the culmination of decades of experimentation.

Lego used to make its main bricks from something called cellulose acetate, but CA bricks tended warp and deform over time; the colour faded.

ABS was the zenith – the ultimate Lego material.But the catch here is that ABS is made from crude oil – well, strictly speaking from both oil and gas.

Every kilogram of Lego blocks in your cupboard or on the toy store shelves began its life as two kilograms of crude oil.Acrylonitrile is made from the ethylene you find coming out of the crackers at oil refineries.

Butadiene you get when you catalyse and dehydrogenate butane.

Styrene comes from benzene.

ABS is in some senses the quintessential petrochemical product.Which is problematic if you have a commitment to sustainability & eliminating carbon emissions, as Lego does.

Their plan was to replace ABS with an oil-free alternative. And a couple of yrs ago Lego announced it had a prototype replacement made from recycled plastic bottles.Problem was, recycled polyethylene terephthalate simply wasn’t quite as good as ABS. Virgin RPET was far too soft, so it needed additives and to be highly processed.

The upshot was its carbon footprint was actually HIGHER than those old oil-based ABS bricks.“In the early days, the belief was that it was easier to find this magic material” chief executive Niels Christiansen told the FT. But “We tested hundreds and hundreds of materials. It’s just not been possible to find a material like that.”

Part of the problem here – one which crops up again and again throughout *Material World* – is that it turns out the suite of materials we tend to use these days are simply VERY good at doing what they do.

For instance:Kerosene is really hard to beat as an aviation fuel.

Methane is a brilliant source of the hydrogen for making, among other things, fertilisers.

Concrete might not be the only strong building material, but it’s incredibly easy to lay and also phenomenally cheap.All these things create significant carbon emissions.

But they are central to modern life. They are a large part of the explanation for how we’ve been able to urbanise and feed billions of people in recent decades.

Finding low carbon replacements will be HARD.In some cases the replacements for fossil fuels are actually BETTER than what they’re replacing.

80 per cent of the energy in petroleum is wasted when you drive your car (mostly as heat). But an electric car loses barely 20 per cent of the energy along the way.(This is not to say there aren’t challenges with EVs. They’re much more mineral intensive to build than than petrol cars. Range & charging speed are still too low and they’re not good enough for carrying heavy loads. But in certain thermodynamic respects they’re better.)

But the lesson from LEGO is that for much stuff, it’s actually proving far more difficult to find deployable zero or low carbon replacements.

It’s just really hard because these old (invariably carbon intensive) industrial substances are really good at what they do.This gets to a critical issue which still isn’t widely appreciated enough.

Replacing some coal fired power stations with wind turbines is THE EASY BIT. The next bit will be far harder (inc making grids work).

Replacing cement manufacture or ammonia production will be FAR HARDERBut unless we can crack this stuff we have no hope of meeting all those pledges our govts have signed up to. On the one hand this is massively daunting.

On the other hand, it makes for an extraordinary industrial challenge the likes of which we haven’t had for centuries.At some point we might solve the Lego conundrum. Or we might not.

On the bright side, at least turning oil into plastic blocks isn’t as pollutive as burning them. But it illustrates how much trickier and stickier these issues are than most people assumeIt also gets to another, deeper point.

For years we were encouraged not to think too deeply about where stuff came from & the compromises along the way.

Products were disposable & ephemeral.

It’s time we thought more about what it takes to make stuff & hence respected it more.Anyway. For more abt the knotty, fascinating realities underlying the world, check out Material World.

Out now in paperback.

It’s actually about all sorts of other random stuff like sand and salt. But with, I think, some important lessons for all of us.

Vir: Ed Conway