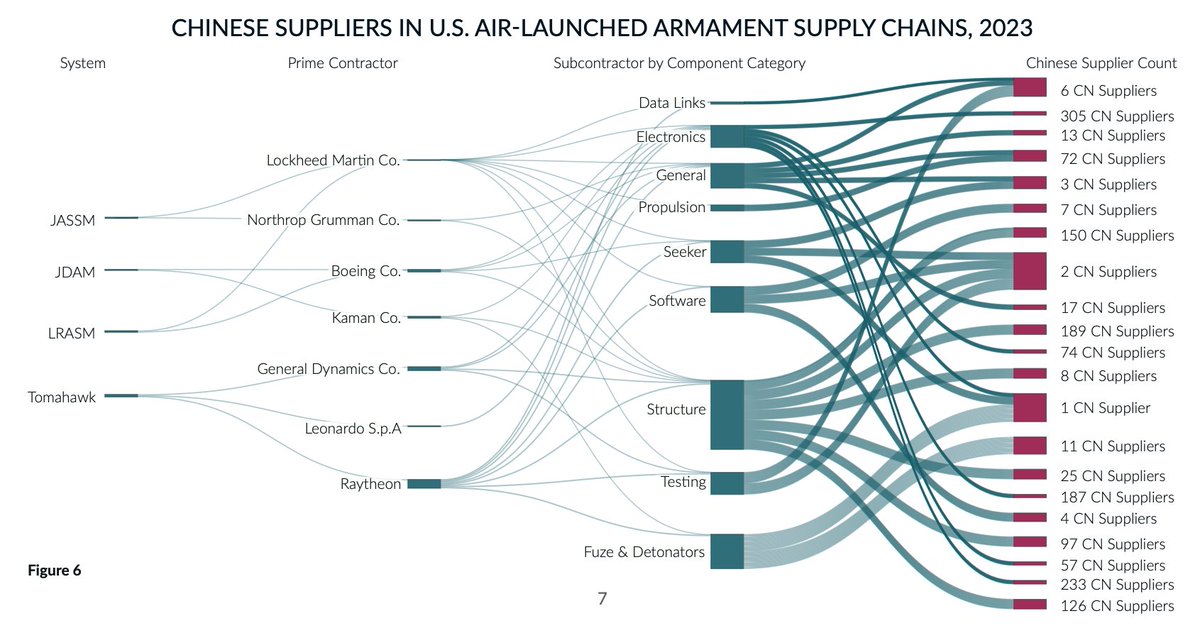

Zelo zanimivo poročilo družbe Govini (*), pogodbenika ameriškega ministrstva za obrambo, o stanju dobaviteljskih verig v ameriški vojaški industriji. Poročilo pravi, da je proizvodnja ključnih ameriških vojaških sistemov kritično odvisna od množice (več kot 42 tisoč) kitajskih dobaviteljev, medtem ko se je sestavljanje orožja skoncentriralo na 25 lokacijah v ZDA. Kot kaže slika spodaj, je vso ključno orožje za zračno bojevanje (od JASSM do Tomahawka) kritično odvisno od kitajskih dobaviteljev (in podobno velja za protizračne sisteme, kot je Patriot, glejte sliko 5 spodaj).

To pomeni resno varnostno tveganje za ZDA in hkrati resno ogroženost ameriških vojaških dobav.

Prvič, če bi prišlo do vojne okrog Tajvana, bi lahko kitajska vlada v trenutku presekala dobave kitajskih dobaviteljev ameriškim orožarskim podjetjem, kar bi omejilo možnosti ameriške vojaške pomoči Tajvanu ali lastne (ameriške) vojaške vpletenosti v vojno.

Drugič, ameriška vojaška industrija je za razliko od prvih dveh desetletij po 2. svetovni vojni glede kapacitet tako osiromašena, da ni sposobna hitrega povečanja proizvodnje orožja v primeru vojne. To pojasnjuje, kako sta obe vojni, v Ukrajini in Gazi, ki ju z orožjem podpira ameriška vlada, skorajda povsem izpraznili ameriška vojaška skladišča, zato v primeru dolgotrajnejših vojn ZDA več ne bodo v stanju vojaško podpirati Ukrajine in Izraela.

In tretjič, če bi se – hipotetično – nekdo odločil resno imobilizirati ameriško vojaško vojno sposobnost, bi bodisi zaustavil dobave sestavnih delov ali pa s ciljano akcijo onesposobil 25 lokacij, kjer poteka sestavljanje ključnih ameriških orožij.

Vzpostavitev dobavnih verig v vojaški industriji je dolgotrajen proces, ki traja več kot desetletje, zato bodo ZDA, tudi če takoj začnejo z “odcepljanjem” od kitajskih dobaviteljev, še dolgo vojaško ranljive in si pravzaprav ne morejo privoščiti globalnega spopada z Rusijo in Kitajsko. Rusija je za razliko od ZDA ohranila kapacitete vojaške industrije po koncu hladne vojne, zato jih je po začetku vojne v Ukrajini dokaj hitro reaktivirala in dodatno povečala. To ji daje prednost pred zahodnimi državami v vojni v Ukrajini, saj so kapacitete slednjih na ravni zgolj okrog ene petine ruskih. Na drugi strani je Kitajska povsem modernizirala vojaško industrijo, ki je z robotizacijo daleč najsodobnejša na svetu, hkrati pa so njene kapacitete orjaške.

Iz tega vidika je ameriško izzivanje Kitajske glede Tajvana ali vabljenje Ukrajine v Nato zgolj navadno petelinjenje, saj si ZDA vojaško ne morejo privoščiti spopada z Rusijo in Kitajsko.

Spodaj je kratek povzetek analize z nekaj ključnimi grafi, ki kažejo ranljivost ameriške vojaške industrije, v nadaljevanju pa sledi še nekaj ključnih poudarkov, zakaj je prišlo do te ranljivosti.

Povzetek

Historically, American industry has risen to the task. For nearly a half-century, the U.S. military had access to an enormous and diverse domestic industrial base. Even when supplies ran low at the onset of the Korean War, a heavily industrialized America was able to ramp up within months to generate torrents of weapons that held off vastly larger Chinese forces for the next three years.

Today, however, U.S. domestic production capacity is a shriveled shadow of its former self. Crucial categories of industry for U.S. national defense are no longer built in any of the 50 states. With just 25 well-constructed attacks, using any of a variety of means, an adversarial military planner could cripple much of America’s manufacturing apparatus for producing advanced weapons.

Under the current U.S. government approach, industry cannot meet production demands to support allies under fire and deter war in the Pacific. Using case studies of munitions and shipbuilding production, this paper delineates the current state of affairs in the defense industrial base and provides pathways to mitigate, if not end, this strategic vulnerability.

…

After elevating the innovation competition as the preeminent military challenge, many defense analysts move next to the readiness of the combat force: the number of aircraft prepared to fly, ships to sail, and infantry to deploy. Yet they also need to consider the readiness of the defense industrial base to mobilize production: how much and how quickly. U.S. leaders must thoroughly assess the capacity of the U.S. industrial enterprise, as compared to China, to produce the weapons and equipment most critical to an Indo-Pacific conflict.

The results will be sobering, if not alarming. In the last five years, Chinese firms have joined the ranks of the largest global defense companies at an accelerated pace. The country’s expanding exports of high-end systems—ranging from armed unmanned aerial vehicles to precision-guided munitions, submarines, and frigates—testify to China’s arrival on the global arms stage.

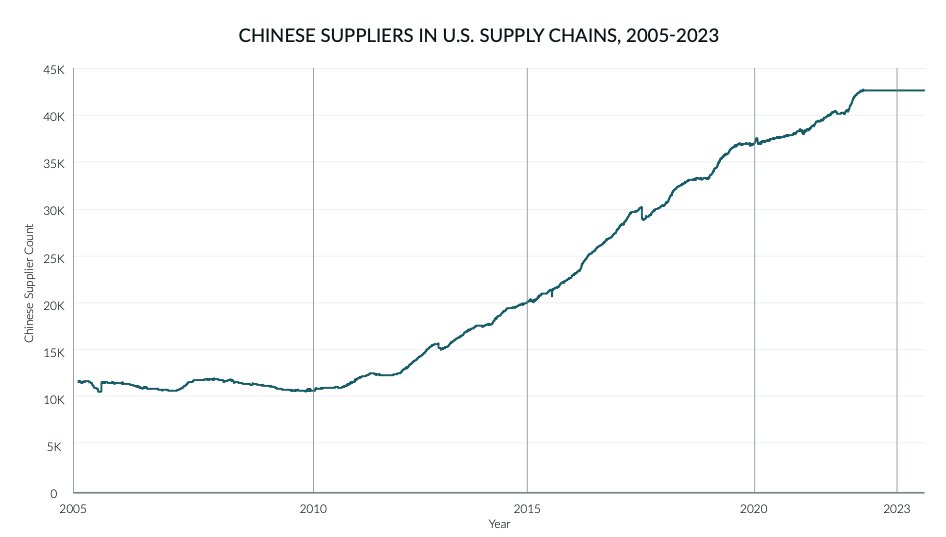

While China cranks out advanced weapons at a prodigious rate, it has also embedded itself in the supply chains for vital components of U.S. military platforms and weapons systems, creating U.S. reliance on the Chinese industrial base. Data from Govini’s Ark.ai, the software system for defense acquisition, shows that between 2005 and 2020, the level of Chinese suppliers in the U.S. supply chains quadrupled (Figure 1). In categories such as electronics, industrial equipment, and transportation, China’s expansion is even more pronounced. Between 2014 and 2022, U.S. dependence on China for electronics increased by 600% (Figure 2).

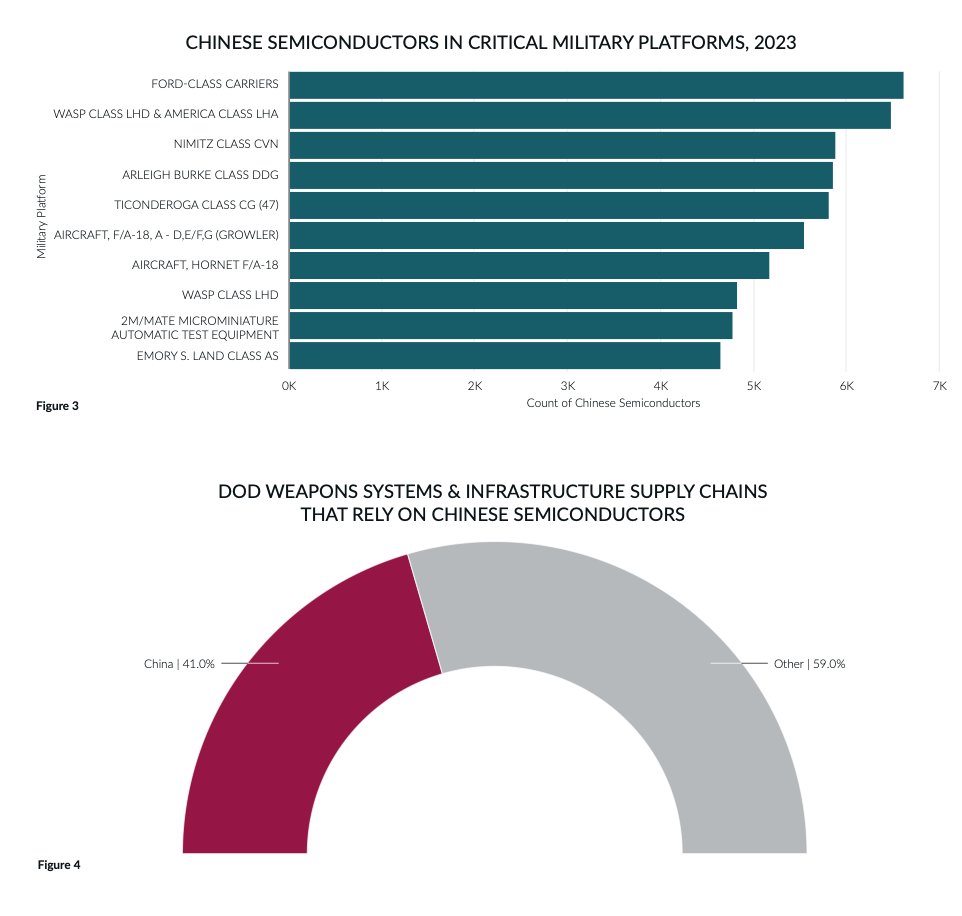

U.S. companies at the bottom of the supply chain pyramid often source these parts from China in open market transactions. As a result, many essential components in sensitive U.S. military systems now come from China. Countless major weapons platforms are vulnerable (Figure 3).

Dependence on China for microelectronics, including semiconductors, packaging, and more, is particularly acute. Embedded in nearly every U.S. weapons system, semiconductors are foundational to U.S. military advantage. During a May 2023 visit to a Lockheed Martin missile factory in Alabama, President Joe Biden told employees that each Javelin anti-tank weapon produced there includes more than 200 semiconductors. Analysis from Ark.ai has found that more than 40% of the semiconductors that sustain DoD weapons systems and infrastructure depend on Chinese suppliers (Figure 4).

Chinese semiconductor suppliers are inextricably linked to vital DoD weapons supply chains, such as the B-2 Bomber and Patriot air-defense missile (Figure 5).

The Path to industrial fragility

How did we get into this predicament? When the Soviet Union collapsed and U.S. military spending shrank, America’s defense companies adjusted by merging and through adopting lean production and other financially driven “efficiencies.” That approach constituted the formula to remain in business. It did not deliver any savings in weapons costs, but instead resulted in a spike of spiraling per unit price increases. Moreover, with the decline in orders and the new business model, weapons stockpiles dwindled along with the production capacity to regenerate.3

As early as 2008, the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments found that the migration toward “a low-volume, tailored-requirement production model” is incompatible with “an industrial surge capability that could turn out large numbers of weapons and systems should the need arise.” The costs for defense firms to maintain excess production capacity have since increased, making it uneconomical under the current governmental acquisition system. Neither Congress nor the Defense Department has been willing to pay companies to maintain such capacity. Both branches of government embraced “just-in-time” inventory practices.4

Indeed, the U.S. government penalizes companies that might do otherwise. The Department of Defense generally pays only for contractor costs closely tied to the product numbers budgeted for the current program. That means the contract has little room to cover company expenses for maintaining facilities, manufacturing lines, parts warehouses, or relevant specialized technicians, engineers, or scientists needed in a contingency to surge production. The Pentagon’s “lowest price technically acceptable” ethos, i.e., spending not a penny more than is necessary to meet the most basic immediate requirements, has brought damaging secondary effects.

Military manufacturing cannot quickly be turned on and off at will. Once DoD orders decline, defense manufacturers necessarily close production lines or reduce them to veritable runts. These companies have few alternatives besides the United States and several other advanced allies to shop their defense-unique wares.

A few mega-sized prime defense contractors sit atop a supply chain pyramid of tens of thousands of mid-to-small businesses. When the first tier curtails throughput, orders to smaller suppliers dry up. Some businesses may entirely close. In fact, many have left the defense industry over the last several decades–deciding to employ their limited time, talent, and capital in the larger and more lucrative commercial sector. Estimates indicate that the number of small to midsize contractors forming the bottom of the pyramid has shrunk from approximately 60,000 to 30,000 over recent decades.

Viri:

[1]: govini.com/insights/numbe

[2]: cdn.prod.website-files.com/65e61e6392aba0

[3]: forbes.com/sites/erictegl

* “The report was issued by Arlington, VA-based Govini which was awarded a five-year $400 million contract from the Pentagon in 2019 to deliver data, analysis and insights into DoD spending, supply chain and acquisition”

You must be logged in to post a comment.