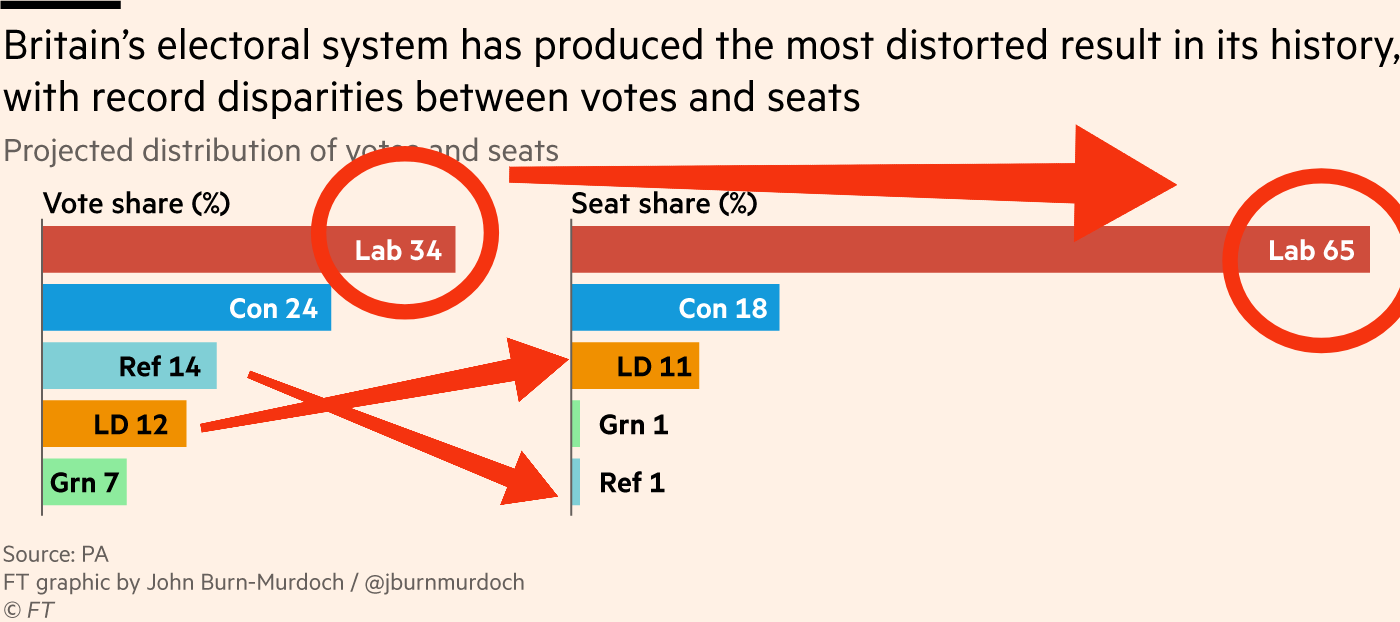

Včeraj je Laburistična stranka v V. Britaniji močno zmagala in po 14 letih z absolutno večino zamenjala konzervativce na čelu države (no, zaradi čudnega večinskega sistema so laburisti ob zgolj tretjini glasov (manj kot 34 %) dobili skoraj dve tretjini sedežev (65 %) v parlamentu, Farageovi populisti pa ob več kot 14 % glasov zgolj 4 sedeže).

Zanimivo je, da so anketirani kot največji (in to s naskokom največji) razlog, zakaj bodo volili za laburiste, navedli, da zato, da “vržejo ven konzervativce“. Konzervativci so zakrivili največjo bedo v sodobni zgodovini Britanije, najprej z neznosno in nepotrebno politiko varčevanja po letu 2010, ki je ultimativno privedla tudi do Brexita (ki so ga konzervativci omogočili), za post-Brexit stagnacijo, za katastrofalno obvladovanje Covid krize in energetske krize po 2022.

No, volilci bi tudi pri laburistih morali paziti na “darila”, ki jih prinašajo. Tako kot so bili volilci navdušeni nad Blairom in njegovo “tretjo potjo”, ki se je nato izkazala kot izrazito neoliberalna in tako kot se je Blair izkazal kof sokreator vojne v Iraku, v kateri so britanske in ameriške enote pobile več kot pol milijona civilistov, se morajo paziti politik “nove” laburistične stranke pod vodstvom Keira Starmerja. In to kljub sloganu “country first, party second“. Starmer se je po eni strani izkazal kot pravoveren sledilec ameriškega administracije tako glede podpiranja vojne v Ukrajini in še bolj glede podpiranja Izraela v vojni v Palestini (pod krinko politike “antisemitizma”; no, “zlobni viri” pravijo, da Starmer in laburisti ne bi nikoli zmagali, če ne bi imeli podpore finančnega kapitala in seveda lobija, ki stoji za njim). Na drugi strani pa je Starmer nakazal, da bo pravoverno sledil ameriškim neoliberalnim politikam tudi na področju financiranja infrastrukture in javnih služb. Kot piše Daniela Gabor v The Guardianu, je Starmer napovedal španovijo z največjim private equity skladom BlackRock “to rebuild Britain” (ja, tistim BlackRock, ki naj bi po mandatu ZDA dobil v upravljanje Ukrajino (sklada za obnovo Ukrajine), če bi Ukrajina slučajno zmagala v vojni z Rusijo). BlackRock ima v lasti precejšen del stanovanjskih nepremičnin v Britaniji, s čimer zaradi visokih najemnin dosega pretežni del svojih prihodkov v Britaniji.

BlackRock naj bi zdaj namesto vlade menedžiral tudi ključne javne investicije v energetiki in infratsrukturi. Razlog, zakaj je Starmer izbral tovrsten način financiranja, je enak skripti iz časov Thatcherjeve in Blaira: proračunski deficit in javni dolg Britanije naj bi bil prevelik in zaradi fiskalnih omejitev naj ne bi dopuščal povečanja javnih izdatkov za investicije, zato naj bi breme financiranja investicij prevzel zasebni sektor. Torej, magična beseda se imenuje javno-zasebno partnerstvo (JZP). No, česar politiki in zasebni investitorji glede JZP ne povedo, je, da so projekti, financirani prek JZP, neprimerno dražji od projektov, financiranih z javnim denarjem. Razlog je v tem, da strošek javnega dolga kot vira financiranja znaša okrog 3 % (realno pa je ob upoštevanju inflacije blizu nič), medtem ko zasebni vlagatelji želijo donose vsaj okrog 10 % (na letni ravni).

Torej, program laburistov prinaša predvsem privatizacijo javnih storitev, stanovanjskega fonda in priložnost za velike zaslužke zasebnemu finančnemu kapitalu. Finančni kapital zato ljubi novo prihodnjo britansko vlado. Vendar ne se čuditi, če nova laburistična vlada ne bo izboljšala blaginje “navadnih Britancev” in če bodo ti čez štiri leta besni na laburiste.

The Labour party has a plan for returning to power: it will get BlackRock to rebuild Britain. Its reasoning is straightforward. A cash-strapped government that wants to avoid tax increases or austerity has no choice but to partner with big finance, attracting private investment to rebuild the infrastructure that is crumbling after years of Tory underinvestment. Labour has already done the arithmetic: to mobilise £3 of private capital from institutional investors, you need to offer them £1 in public subsidies. But every time you hear Labour announce such an infrastructure partnership, think of the hidden politics. BlackRock will privatise Britain – our housing, education, health, nature and green energy – with our taxpayer money as sweetener.

BlackRock has long peddled the idea of public-private partnerships for infrastructure, climate and development. Yet its political momentum has recently accelerated. When its chair, Larry Fink, the world’s most powerful financier, sat with world leaders at the G7 summit last month, he promised the following: rich countries need growth, infrastructure investment can deliver that growth, but public debt is too high for the state alone to invest the estimated $75tn (£59tn) necessary by 2040. Trillions, however, are available to asset managers who look after our pensions and insurance contributions (BlackRock, the largest of these firms, manages about $10tn, as a shrinking welfare state pushes us – future pensioners – into its arms).

If governments work with big finance, Fink explained, they can unlock these trillions. But to do so, they will need to mint public infrastructure into investable assets that can generate steady returns for investors. Why does BlackRock need the state? Why can’t it deploy trillions without the government’s helping hand? The British public remembers all too well PFIs, the private finance initiatives through which the state ended up paying extortionate amounts to private contractors that designed, built, financed or operated public services such as prisons, schools and hospitals before handing them back to the state, often in poor condition.

But for big finance, there is more now at stake. In this golden age of infrastructure, financiers plan to own our infrastructure outright and transform it into a source of steady revenue. Since buying Global Infrastructure Partners in January 2024, BlackRock holds about $150bn in infrastructure assets, including US renewable energy companies, wastewater services in France and airports in England and Australia. It plans to expand aggressively, just like other private infrastructure funds. Direct ownership is the main game, but not the only one. Big finance can also invest in infrastructure indirectly, by lending to private infrastructure companies. The key is returns. For this, BlackRock wants the state to “derisk” investments. This financial jargon was included in the 2024 Labour manifesto, and it in essence involves the state stepping in to improve the returns on infrastructure assets.

The choice here is not merely between public and private financing of public goods, but whether British citizens should tolerate the government handing out public subsidies for privatised infrastructure. Housing is only one example of the areas where these investors can already be glimpsed. Institutional landlords – the most prominent being Blackstone, the private equity fund – can acquire residential housing by participating in the privatisation of public housing. After the global financial crisis, the firm also bought up nonperforming mortgages, and since then it has gone on a global shopping spree, snapping up homes across the US and Europe. In the past year, Blackstone bought new rental homes in Britain worth about £1.4bn from the housebuilding company Vistry.

Look behind Blackstone’s returns – which come from rents and rising house prices – and you will find the state’s footprint. The government has helped to guarantee and derisk these returns through regulations that favour asset owners over renters, through economic policies that support house price inflation and through the provision of income support – such as housing benefit – that allows renters to continue paying their institutional landlords. Although we’re told that partnering with these investors is a means of solving the housing crisis, it often delivers the opposite: higher rents, the displacement of lower-income tenants who are often from minority groups, and less affordable housing. This explains the backlash against institutional landlords, from Copenhagen to Berlin, Dublin and Madrid. Yet such public pressure will only be effective once the state returns to building public housing.

Labour’s strategy raises a bigger set of questions about the type of state we want. Starmer’s vision for government-by-BlackRock reduces the question of state capacity to “how do I get BlackRock to invest in infrastructure assets?” This model involves the state in effect subsidising the privatisation of everyday life. This doesn’t only make it harder to bring public goods back into public ownership; it also allows big finance to tighten the grip on the social contract with citizens, and to become the ultimate arbiter of climate, energy and welfare politics, which will have profound distributional, structural and political consequences.

Already, BlackRock is betting on becoming a key provider of green energy infrastructure – though its actual commitment to tackling the climate crisis only extends so far. The firm has lobbied heavily against European proposals to regulate its lending to fossil fuel interests with penalties, and has instead called for voluntary climate commitments. It is aiming to rapidly grow its green energy profits by tapping the government subsidies that will probably be provided through Starmer’s GB Energy, and through the US Inflation Reduction Act.

But the profits BlackRock will hope to generate through investing in green energy are likely to come at a huge cost. In Britain, we know that the public ownership of green energy is more effective at lowering consumer bills, accelerating the green transition and creating good jobs. The risk is not only that our climate future will be vastly more expensive if actors such as BlackRock are driving it, but that this future will also produce a more unequal society, where citizens equate green measures with unaffordable public services. This may well provide the kindling for authoritarian, far-right fossil-fuel politics that reject the green transition and frame it as an assault on people’s living standards.

Instead, we should plan creatively for a future where extreme climate events necessitate permanent state intervention, from price controls to buffer stocks and public ownership. What’s needed is a big green state. For this, we first need to repair a serious failure of macroeconomic policy imagination that regards the public purse as too small to fund transformative public infrastructure. To do so will require a radical transformation of the state. The state that Rachel Reeves, the likely future chancellor, promises us must break down the neoliberal walls between monetary, fiscal and industrial policy, and scrap low-tax regimes for multinational corporations and individuals with high net worths. It must shrink the power of big finance. This would be a gigantic undertaking, but it is the only realistic one we have.

Vir: Daniela Gabor, The Guardian

You must be logged in to post a comment.