Ekonomisti se že dve leti prerekajo, ali je bil inflacijski šok v zadnjih dveh letih povpraševalne ali ponudbene razlage. Postavitev prave diagnoze glede tega ni trivialna in nepomembna zadeva. Napačna diagnoza namreč lahko vodi v napačen način ukrepanja. Če je bil inflacijski šok povpraševalne narave zaradi pregrevanja gospodarstva in posledičnega vpliva na rast plač, je pravilni protiukrep dvigovanje obrestne mere s strani centralnih bank, dokler dražji krediti ne ohladijo zasebnega in investicijskega povpraševanja. Če pa je bil inflacijski šok ponudbene narave (zaradi denimo pomanjkanja in posledičnega dviga cen surovin, hrane in energentov), potem centralne banke proti temu ne morejo narediti nič, saj ne morejo “natiskati” čipov, nafte, plina, aluminija itd. Dvigovanje obrestnih mer, da bi zaustavili tak tip inflacije je absolutno napačen ukrep, saj deluje kot “napalm metoda” – da bi se znebili koloradksih hroščev z napalmom po nepotrebnem požgemo celo polje in uničimo letino.

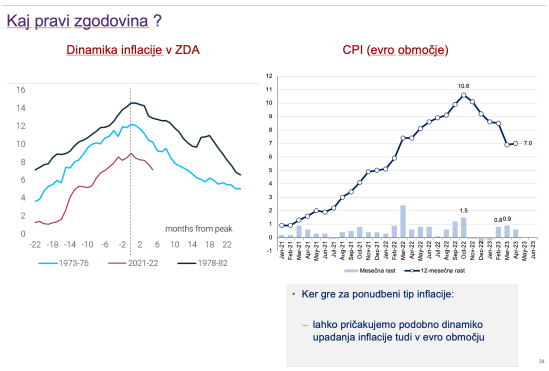

In natanko to danes centralne banke počnejo – inflacijski šok ponudbene narave poskušajo “zdraviti” kot da bi bil povpraševalne narave in s tem gospodarstva po nepotrebnem tiščojo v recesijo. Če je bil inflacijski šok ponudbene narave, bo inflacija upadla, ko se bodo umirili dejavniki, ki so inflacijo zagnali – torej cene energentov, surovin in hrane. In točno to se v zadnjega pol do tričetrt leta dogaja. Inflacija upada, ker so upadle cene energentov in ker so se zamaški v dobavnih verigah sprostili. Preostanek inflacije je ostal le še v povišani rasti cen hrane. Vendar se bo tudi ta rast umirila v času poletne sezone. In če ne bo novih šokov (kot je bila denimo Ukrajinska vojna), se bo ponudbena inflacija, kot sem zapisal v včerajšnjem komentarju glede astroekonomske napovedi inflacije, iznihala v 18 mesecih po doseženem vrhu. To pa je konec letošnjega leta v ZDA in spomladi naslednje leto v EU.

Spodaj lahko preberete podoben komentar s strani Martina Sandbuja v Financial Timesu, ki navaja dve zadnji raziskavi ekonomskih veličin glede narave inflacije (Bernanke & Blanchard, 2023; Guerrieri et al, 2023) in ki svarita pred tem, da bi lahko sedanji ukrepi centralnih bank vodili v preveč in nepotrebnega zategovanja.

Here is a condensed description of how the rise in inflation — known to non-economists as the cost of living crisis — has recently been playing out: headline inflation has peaked across most advanced economies, but core inflation (excluding volatile food and energy prices) and price growth in services haven’t, and are even continuing to intensify in some places. Until this week, that was a pretty accurate summary, and an awkward one for those who, like me, have argued that our maximally unfortunate series of inflationary shocks will soon go away by themselves — against those who argued that bad macroeconomic policy was to blame.

But in just the past few days, larger than expected drops in inflation — including for services — in Germany, Spain and France show that the one-off temporary shocks explanation should not be discarded yet. We are still fumbling for the answer to the single most important question in finding the right policy response to rising prices and hence judging the performance of our central banks. But two new pieces of research shed more light on the question.

A recent high-powered event at Brookings covered the US situation. Two giants of the field, Olivier Blanchard and Ben Bernanke, presented a paper assessing what was the early argument of those warning against inflation: that excessive fiscal stimulus would overheat labour markets, drive up wages and hence prices. Their summary conclusion is politely put: “The critics’ forecasts of higher inflation would prove to be correct — indeed, even too optimistic — but, in substantial part, the sources of the inflation would prove to be different from those they warned about.” Less politely, the critics’ predictions were right for the wrong reasons.

That matters because your policy conclusions depend on the reasons why inflation rose. Bernanke and Blanchard find, essentially, that labour markets were the dog that didn’t bark. Labour market tightness only accounts for a sliver (the red segment of their column chart, reproduced below) of inflation above the Federal Reserve’s target of 2 per cent since the end of 2019. In contrast, almost the entire inflation dynamics are attributable to energy and commodity shocks (the blues) and, in the early pandemic recovery, supply chain snarl-ups (yellow).

To be clear, Bernanke and Blanchard are not saying that labour market tightness is no concern and inflation will go away entirely by itself. Indeed, they warn that labour market-driven inflation is more persistent and that policy should, therefore, bring supply and demand into better “balance”. But their analysis entails that this particular problem is small — in my view so small as to be negligible, or at least far from justifying the sharp tightening the Fed has undertaken. Eyeballing their chart, labour market tightness is responsible for about 0.5 percentage points of the above-target inflation rate.

And in my judgment they have, if anything, stacked the deck against a transitory interpretation of the price growth we see. They calibrate the effect of a high job vacancy rate against pre-pandemic data, not allowing for the possibility that a large-scale reallocation process is making a higher than usual vacancy rate compatible with less inflationary wage growth. (We can throw into the mix recent Fed research — hat tip: Torsten Sløk — showing that labour costs are “responsible for only about 0.1 percentage point of recent core PCE inflation”.)

I take this research, then, to support the view that our current inflationary episode is mostly down to a series of negative supply-side or demand-composition shocks — it is not the consequence of outsize aggregate demand. It also suggests there is reason to expect the current deceleration in prices to continue of its own accord, and perhaps to worry that once the effects of the past year of tightening hit the economy, they may prove excessive.

I draw similar lessons from another important piece of state of the art research: the more Europe-focused work on the nature of our current inflation of this year’s Geneva Reports, at present circulating in draft form. I recommend looking at the public presentation slides from the authors Veronica Guerrieri, Michala Marcussen, Lucrezia Reichlin and Silvana Tenreyro.

Their main message is to pay attention to how cost-driven inflation does not affect all sectors equally (unlike, to some extent, aggregate demand shocks). Energy prices, which they take as their main focus, obviously drive up costs more in some sectors than others, depending on their energy intensity — think transportation relative to retail. But the outputs of one sector are inputs into another sector — shops pay for transport.

(The same point can be made — and is made by Bernanke and Blanchard — about the most striking phenomenon in 2021, the huge swing in the composition of US consumer demand from services to goods: running up against production constraints in one sector brings more inflationary pressure than slack in another sector can bring offsetting deflationary pressure. But that is not a sign overall aggregate demand is excessive.)

This means cost shocks can cascade through the economy for some time: “a supply shock that hits different sectors differently generates lagged waves of sectoral inflation that make the response of aggregate inflation persistent”.

It is key to notice, too, how much bigger the supply shocks have been in Europe than in the US — and how correspondingly longer it will take for the waves to dissipate. The Bank of England’s Jonathan Haskel found a good way to express how big that difference is in a speech last week:

In the US, the wholesale price of pipeline natural gas, expressed in terms of barrel of oil equivalents, rose from around $10 over 2020 to $50 in August 2022, before falling back to $12.50 in April 2023. In Europe, it has risen from approximately $20 per barrel of oil equivalent to $80, although at its peak it was just over $400 in August 2022.

And as Guerrieri and colleagues point out, dearer energy is a terms of trade loss for Europe — it makes it poorer on the global stage — but a (moderate) gain for the US.

A further implication of their analysis is that mistaking lagged waves of sectoral (one-off) inflation for entrenched aggregate inflation risks a policy error: coming down too hard on inflation hinders the relative price changes that are necessary for the market economy to allocate resources to where they are most needed. And that comes on top of the “aggregate” error of tightening so much that it kills growth and destroys jobs unnecessarily.

I think a big takeaway from the latest research is that there is a serious problem of “observational equivalence” in our current inflation episode. Two years, with multiple supply-side disruptions, is simply not long enough to establish whether we are still just seeing the one-off shocks working their way through the economic system or a rise in underlying self-perpetuating inflation. It is certainly not long enough to dismiss — as most have now done — the possibility that we are still simply working our way through an unexpectedly long sequence of particularly nasty one-off cost shocks. The latest signs that falling energy prices are pulling broader inflation back down on both sides of the Atlantic corroborate that view — if they continue.

Vir: Martin Sandbu, Financial Times

You must be logged in to post a comment.