John Cochrane v razumnem komentarju lepo razloži Bernankejevo izjavo, zakaj QE (lahko) deluje v praksi, ne pa tudi v teoriji. Razlika med ameriškim in evropskim QE je v tem, da je v ZDA Fed s tem signaliziral, da bodo obresti še dolga leta ostale nizke, v EU pa je ECB signalizirala, da bo odkupovala državni dolg (s čimer se zmanjšujejo tveganja). In Cochrane brez dlake na jeziku pove, da je pretvarjanje ECB, da s tem, ko nacionalne CB odkupujejo nacionalni dolg, ECB ne prevzema tveganja, kratkega daha. V primeru, da denimo španska CB bankrotira zaradi odkupov španskega dolga, jo bo morala reševati ECB. Prejšnji četrtek smo torej skozi stranska vrata dejansko dobili evroobveznice v preobleki diplomatske centralnobančne latovščine.

Ben Bernanke famously said that QE works in practice but not in theory. What that means, of course, is that the standard theory is wrong, and to the extent it “works” at all, it works by some other mechanism or theory. Permanent price impact by changing the private sector portfolio composition is the “theory” that Bernanke acknowledges really makes no sense. So why might a QE work?

In the US case, QE was arguably a signal of Fed intentions. Buying a trillion dollars of bonds and issuing a trillion dollars of, er… bonds (reserves are floating-rate debt) is a way for the Fed to tell markets that it will be years and years before interest rates go up. As I chat about QE with economists, this pretty much surfaces as the most plausible story for QE effects (along with, there weren’t any long lasting effects.) Greenwood, Hanson, Rudolph, and Summers make this point nicely, showing that Fed-induced changes in maturity structure have about twice the effect that Treasury selling more bonds does — though exactly the same portfolio effect.

But what is the signal in ECB QE? Well, a decidedly different one. The signal is, I think, not about interest rates, but that the ECB will buy government debt. “What it takes” is now taken. Yes, there is this lovely pretense that national central banks buy the bonds, so the ECB doesn’t hold credit risk. But if a country defaults, where is the national central bank going to come up with funds to pay the ECB?

So, when we think of what expectations people derive from ECB QE, and with that how it might or might not “work,” the obvious conclusion is that the Eurobonds are now being printed. Like all bonds, they will either be repaid, inflate, or default.

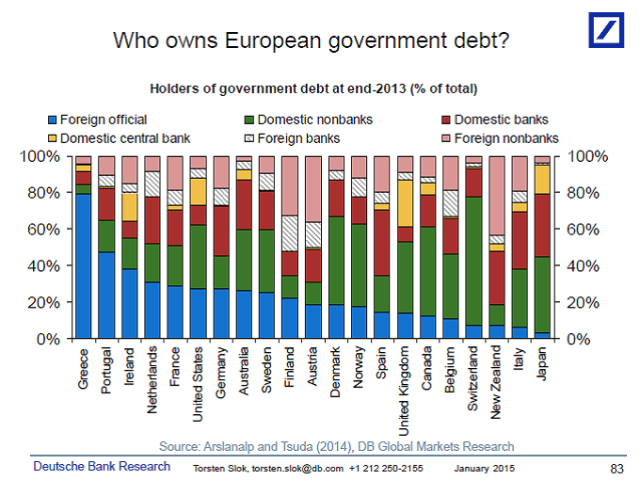

Torsten Slok sends on this interesting graph. 80% of Greek debt is now in the hands of “foreign official.” Now you know why nobody is worrying about “contagion” anymore. The negotiation is entirely which government will pay.

Vir: John Cochrane

Priporočam, da preberete tudi prvi del komentarja o švicarskem QE prek vezave franka.